Stop Torture in Health Care

By Daniel Wolfe

Throughout Southeast Asia, men and women who are caught using drugs are locked away in so-called rehabilitation centers where they are routinely tortured. Many are raped by guards, smacked with “the stick” as a cure for drug addiction, or beaten if they get sick or fail to meet their labor quota. In Cambodia, as noted this week in an op-ed by Human Rights Watch’s Joe Amon in the Bangkok Post, drug users report being shocked with electric batons, whipped with braided wire, or chained in the hot sun.

Advocates who work to improve the health of marginalized and criminalized people like drug users and sex workers must navigate a series of schizophrenic policies. On the one hand, international health agencies and public health experts affirm that these populations are at greatest risk for HIV and are in need of targeted, evidence-based health care services. On the other, law enforcement officials and their allies see the same people primarily in terms of their participation in illegal patterns of exchange. In this paradigm, for example, drug users—viewed as morally and legally suspect rather than as in need of services—are usually treated like illicit drugs themselves, as something to be isolated, controlled, and contained. While some term this a “balanced” approach, the reality in most countries is that law enforcement gets more resources and political support.

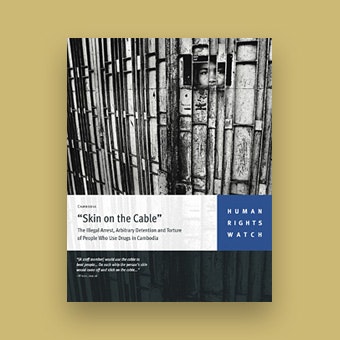

The human costs of this approach were highlighted in two Human Rights Watch reports released on drug detention centers in China and Cambodia. In these countries, as in Malaysia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam, detention centers are misleadingly labeled as “rehabilitation” centers—places of treatment. Yet they are run by military and police rather than medical professionals; include little or no health assessment of detainees; and often offer no treatment save military-style drills, forced labor, and chants such as “drugs are bad, I am bad.”

In Skin on the Cable, the Human Rights Watch report on Cambodia, one drug user recounts his experience:

On one occasion, I got shocked by a [electric] baton. It made me faint for a minute. It was the staff [who shocked me]. They said ‘You know you aren’t allowed to smoke.’ It’s like a burning sensation, real pain, you are shaking. It made me fall down to the ground.... I’ve been shocked three or four times. You get it for smoking, arguing, fighting. They have a couple of batons they leave on a wall charging.

Unlike prisoners, most drug users interned in these facilities have no right of appeal, never appear before a judge, and have received little attention from human rights monitors. Frequently, they also have no access to HIV or TB medicines, or in some cases, even to adequate food.

Virtually 100 percent of those interned in detention camps using this approach return to drug use when they get out, though in some places detention lasts for as long as five years.

The Open Society Institute’s Public Health Program and many of our grantees are engaging governments and international agencies to stop all forms of torture and ill treatment in health care, especially these most egregious cases of abuse masquerading as “public health.” Drug users demonstrating at a recent harm reduction meeting in Bangkok put it simply: chaining, flogging, and forced labor are not treatment.

One can only hope authorities in Southeast Asia, and the UN experts advising them, achieve the same clarity soon.

Until December 2021, Daniel Wolfe was director of the International Harm Reduction Development Program at the Open Society Foundations.