Youth, Politics, and the Inheritance of Progress in Senegal

By Marta Martinelli

“We are ready to be imprisoned, tortured and die if necessary. Enough is enough.” This is the clarion call of a non-violent Senegalese youth movement collectively known as Y’en a marre (Enough is enough).

They are in their early 20s, wear baggy clothes, and have unruly hair at times hidden under distinctive woolen hats—a far cry from the series of diplomats, politicians, analysts, and religious authorities our delegation met in September as part of a visit to Senegal to investigate the political landscape ahead of next year’s elections. This group of less-traditional interlocutors is inspired by Senegal’s hip-hop and rap artists and is bent on preventing their President from “manipulating the constitution and presenting a third, unconstitutional candidature.” They are also actively promoting civic education through their music.

The severity of their message belies the common image of Senegal, a country known for its beaches, comparatively well developed infrastructure, the harmonious coexistence of religious and linguistic groups, and a tradition of democratic elections held regularly since it gained independence fromFrance in 1960. This is the image that makes it a “donor darling” and a driver of change in West Africa, a region otherwise characterised by unconstitutional changes of power (euphemism for repeated coup d’état), massacres, and endemic poverty amidst an abundance of natural resources.

It is also a country where a majority of the population of just over 12.5 million is under 25. In electoral terms this equals more than a million new voters since the 2007 elections and a youth vote that could tip the scale in the ballots scheduled for the end of February 2012. President Abdoulaye Wade is all too aware of this nascent political force.

The Socialist Party’s 40-year domination came to an end in March 2000, when Wade, the leader of the Senegalese Democratic Party (PDS), won the presidency. One year later, free and fair legislative elections conferred a parliamentary majority to the President’s coalition. The 2007 presidential and legislative elections, facilitated by an opposition boycott, maintained the configuration. However the government’s inability to deliver and the deteriorating socio-economic situation resulted in the opposition making substantial gains in nationwide local elections in 2009.

During his tenure Wade has worked tirelessly to turn Senegalinto a “family-run patrimonial state.” To preserve it, he has tried to change the constitution twice and intends to run for president in 2012, when he will be 84. Opinions differ on whether the constitution allows him to do so, and the final verdict on his eligibility rests with the Constitutional Council. Their decision is due only one month ahead of the elections. In the meantime, the opposition has become polarized and divided: several opposition platforms exist, testimony to Senegal’s rich political participation and civil society activism, but they are unable to come forward with a unified agenda, let alone agree on a common candidate.

Challenging commonly held assumptions about the country and highlighting the dangers of democratic relapse, is not an easy task. Power squabbles have intensified and have taken on life-or-death importance. There is a dearth of practical solutions to unavoidable yet predictable problems.

Take rainfall for example. In August 2009, 360,000 people were affected by country-wide floods. The lack of a functioning drainage system largely contributed to the catastrophic results. Since then there has been no progress and thousands of families were displaced during the storms this year. Electricity is another issue; Senegalese experience daily power-cuts that last for hours due to a deteriorating infrastructure that needs investment—a costly undertaking. The economy remains stagnant but no structural policies have been set in place to diversify agricultural production. Security in the Casamance region, where a separatist movement has been active since the early 1980s, is fragile at best. A peace agreement signed in 2004 after 20 years of rebel activities has only resulted in conflict limbo: no war but no peace either.

More importantly, the political culture developed in Senegal through decades of peaceful interreligious cohabitation, media freedom, high levels of education, and a vibrant and well organized civil society seems to have been weakened under Wade’s presidency. The spirit of a recent law on decentralization appears to have been ignored as the government has reconfigured electoral districts and replaced locally elected authorities with nominated officials. The distribution of electoral cards is contingent upon receiving an identity card and there is a strong suspicion that administrative impediments are set in place to delay their delivery. Voters’ registration is slow, more difficult in remote areas, and opposition parties often do not have the means to reach their constituencies or be present at registration. Organizational chaos is threatening the legitimacy of the elections and undermining the opposition’s confidence in the possibility to win free and fair elections. To make matters worse, media harassment has increased.

Senegal’s long-standing relations with donors make their engagement of paramount importance. The U.S., Switzerland, Canada, the United Nations, the European Union, Germany, and some private foundations have been actively engaged monitoring the electoral process and ensuring implementation of corrective measures. The government has yet to pronounce itself clearly on international election monitoring: declarations by official representatives seem to indicate some openness to the idea whilst official invitations have yet to be issued.

Senegal’s largely democratic and peaceful trajectory is an extraordinary achievement that sets it ahead of many African countries. This legacy is at risk of being lost under political imbroglios. It is in the best interest of Senegal, the entire region, and of the donor community, that the country’s positive inheritance reaches the next generation.

Underneath their baggy pants and woollen hats, the youth may not have all the answers, but they are key to the future.

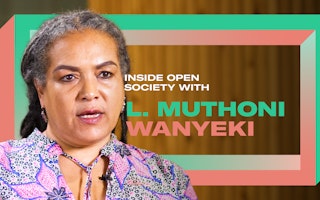

Until February 2022, Marta Martinelli was head of the EU external relations team for the Open Society European Policy Institute.