Yildirim v. Turkey

Wholesale Blocking of Websites Violates Article 10 of the European Convention

A court in Turkey issued an injunction blocking access for all Turkish-based Internet users to the entire Google Sites domain, supposedly to block access to a single website which included content deemed offensive to the memory of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the founder of the Turkish republic. A challenge has been was brought to the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) by the owner of an unrelated academic website that was also blocked by the order, arguing that such an interference with the free flow of information online amounts to “collateral censorship.” The ECtHR found that this violated the right to receive and impart information regardless of frontiers, given the importance of the internet for freedom of expression, and that such prior restraint must be subject to most careful scrutiny and follow a particularly strict legal framework.

Facts

Ahmet Yildirim, a PhD student in computer engineering at Bosphorus University, set up and operateds a website to share information about his academic work and interests. He relieds on sites.google.com, a Google service, to operate, update and host his personal site.

In June 2009, a Turkish criminal court, acting on the motion of a public prosecutor, issued an injunction ordering the blocking of a Turkish-language site also hosted by Google Sites, called Kemalist Abdominal Pain, which hads a clear anti-Ataturk, ridiculing slant. A 2007 statute authorizes courts to block access to foreign-hosted websites where there is “sufficient ground for suspicion” that the content is in breach of eight specified criminal offenses. These include a 1951 law that makes it a crime to “insult the memory” of Ataturk (who died in 1938).

The first instance court issued an order blocking only the specific offending website. Shortly after this injunction, the applicant tried to access his personal site, but was unable to do so, receiving a screen notice that access to the site was blocked on the basis of the above court order. It appeared that the entire Google Sites domain had been blocked.

The applicant appealed the injunction and the blocking of the Google Sites domain. He argued that his page had nothing to do with the offending site, and that the blocking of the whole of Google Sites was excessive, unlawful, and in violation of both the Turkish Constitution and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

On appeal, a Denizli appeals court confirmed the injunction on the basis that it was not technically possible to block access to the offending site alone, and that such a result could be obtained only by blocking access to the entire Google Sites domain. There is no indication that there was any attempt by the Turkish authorities to contact or serve notice on Google. Inc, the owner and operator of Google Sites.

Open Society Justice Initiative Involvement

The Justice Initiative filed third-party comments with the European Court of Human Rights, explaining comparative standards and relevant international law.

Arguments

Prior restraint. Under European law and practice, orders blocking access to online content should be treated as a method of “prior restraint,” and as such should be subject to “the most careful scrutiny.” Internet blocking orders must be strictly necessary and capable of protecting a compelling social interest. The need for such measures must be convincingly established, and they should be adopted only as measures of last resort. The refusal of foreign access providers to take down any objectionable content cannot be a sufficient basis, in itself, for granting blocking injunctions. In European practice, blocking orders against political expression protected by Article 10 are practically unheard of.

Collateral censorship. It is technically possible to block solely the offending website. Blocking orders that indiscriminately prevent access to an entire group of websites amount to “collateral censorship” which should be avoided as unnecessary and disproportionate. No other European country is involved in collateral blocking of entire web platforms, and such cases have not come before the courts, which testifies to their truly exceptional nature. The fact that practically all blocking methods currently available are susceptible to circumvention by average users is relevant as to whether they can be considered “strictly necessary.”

Remedies and Procedural Safeguards. Domestic laws should provide robust and prompt remedies against blocking orders in order to safeguard against unnecessary and disproportionate interferences with Article 10. European standards generally require prior notification of blocking orders to internet service and content providers and grant them a right to prompt judicial review of any interim measures in adversarial proceedings.

The Court held that blocking access to the applicant’s website amounted to an interference with his Article 10 rights to receive and impart information “regardless of frontiers.” The Court reiterated that access to online content “greatly contributes to improving the public’s access to news” as well as expressing and disseminating their views; the Internet “has now become one of the main ways in which people exercise their right to freedom of expression and information.” In this respect, Article 10 guarantees the rights of “any person,” irrespective of their identities or the nature of their speech online.

The Court further found, in line with the Justice Initiative’s arguments, that an interference of this nature amounted to prior restraint and must therefore be subjected to the Court’s “most careful scrutiny.” Reviewing the facts of the case, the chamber held that Turkish legislation did not clearly authorize the kind of wholesale blocking implemented in this case, and that in dictating the method of blocking of illegal online content, the judges had granted too much discretion to an executive agency.

The Court concluded that these shortcomings made the interference “arbitrary” and “not prescribed by law” within the meaning of Article 10(2): all measures preventing access to online content must be in conformity with “a particularly strict [national] legal framework concerning the delimitations of the ban and providing for effective judicial review against potential abuse.”

The Court also commented on the lack of procedural guarantees highlighted by the Justice Initiative intervention, noting e.g. that Google Sites had not been informed of the blocking decision or granted an opportunity to challenge it, and that the domestic courts had failed to consider whether less invasive blocking measures could have been adopted. Whenever adopting blocking measures, national authorities should consider whether they render inaccessible “a large amount of information that would significantly affect user rights” or have other serious side effects.

Judgment delivered by the ECtHR (available only in French).

Written comments filed by the Justice Initiative.

Case is communicated to the Turkish Government, jointly with Akdeniz v. Turkey.

Application filed with ECtHR.

Denizli appeal court upholds the injunction.

Denizli criminal court issues an injunction blocking access to the site ridiculing Ataturk.

Related Cases

Kasabova v. Bulgaria

The case, involving a journalist found liable for criminal libel, raised questions about the burden of proof and liability standards that ought to apply in criminal defamation proceedings.

Romanenko v. Russia

This freedom of expression case before the European Court of Human Rights deals with a Russian newspaper ordered to pay libel damages for quoting local officials.

Related Work

Open Society Justice Initiative Sues U.S. Government for Khashoggi Records

A lawsuit filed in federal court in the South District of New York seeks the immediate release of government records relating to the killing of U.S. resident and Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi.

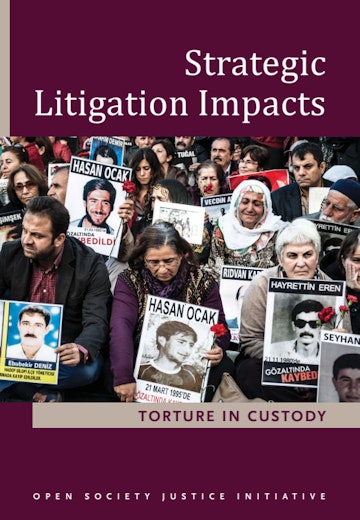

Strategic Litigation Impacts: Torture in Custody

This study looks at how activists in Argentina, Kenya, and Turkey have sought to use the courts to secure remedies for torture victims and survivors, bring those responsible to justice, and enforce and strengthen the law.

Case Watch: European Rights Court Lags on Access to Legal Counsel for Criminal Suspects

A ruling from Europe's human rights court failed to reinforce a growing consensus on the right of suspects in police custody to be guaranteed early access to legal counsel.