Amidst UNESCO Scandal, President Obiang Gives Schools Notebooks in His Image

By Ken Hurwitz

In the last several months, the UNESCO-Obiang Prize in Life Sciences has generated more controversy than the organization has seen in decades. Nobel laureates, previous UNESCO honorees, journalists, scientists, parliamentarians, human rights defenders, and ordinary people have all joined in criticizing the award.

It seems that almost everyone who hears about it is moved to protest the disconnect between UNESCO’s noble mission and its cuckoo plan to slap its name onto a science prize named for and funded by President Teodoro Obiang, a dictator linked to criminal or regulatory money-laundering investigations in three countries, a man whose 31-year reign has saddled the country with some of the worst health and development indicators in the world—despite oil revenues that put its per capita GDP in line with Italy or Spain.

Facing a global outcry against the award, Obiang has tried to fire back with some good old-fashioned do-gooding to prove he is a worthy namesake.

As any good philanthropist would do, the president looked around and saw a critical need no one was filling—the country’s educational system. It certainly could use the help: net enrollment in primary education dropped from 96.7 percent in 1991, prior to the discovery of oil, to 69.4 percent in 2007, in a school system often described as corrupt and incompetent. In 2009, for example, the U.S. Department of State reported that “[t]eachers with political connections but no experience or accreditation were hired even though they seldom appeared at the classes the purportedly taught.”

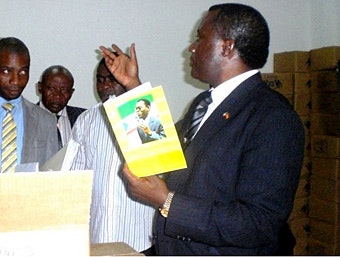

It’s also a school system whose budget—4 percent of government expenditures, lowest portion in the world according to UNDP—apparently can’t even cover the cost of notebooks for the kids. So the president generously “donated” from his own pocket a "wealth of" notebooks for every one of the country’s school districts. And in case the kids or their parents have trouble remembering who their benefactor was, the president thoughtfully placed his own picture on the cover.

Still, you might say, at least the notebooks seem to have gotten to the kids. But last week also saw another, harsher side to the government’s educational interventions. On October 3, twelve eager high school graduates gathered at Malabo airport to head off to Spain and begin their long-awaited university education. Chosen from a group of 300 top-performing students in a transparent, merit-based process, Spain had agreed to finance the students’ studies as part of a program established last year between the two governments.

But, unfortunately for the students, a key government figure was left out of the selection process—Education Minister Filiberto Ntutumu Nguema, the former secretary-general of President Obiang’s ruling “Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea” (PDGE) and campaign manger of the president’s landslide 95.6 percent re-election victory last November. Just as the students were getting on the plane, EG security forces, reportedly acting on the orders of the Minister, barred them from boarding and confiscated their passports. The same thing happened to another group of students the following day. Opposition political figures accused Ntutumu of throttling the scholarship program because he opposed an objective selection process, preferring, instead, to control allocation, directing scholarships to the politically favored and/or those who would pay for them.

You can take that opposition view with a grain of salt. But we do know how the U.S. scholarship programs financed by the oil companies in 2001–2003 were run: after a close look at the programs, a U.S. Senate subcommittee found that “Many of [the 100-plus EG students receiving the scholarship] appeared to be children or relatives of wealthy or powerful E.G. officials,” and these silver-spooners apparently didn’t have to fret about academic pressures. Only five of them, bank files showed [view pdf] (see Annex 18), were able to maintain the supposedly required minimum “B” grade average.

Until November 2021, Ken Hurwitz was senior managing legal officer with the Open Society Justice Initiative.