Forensic Evidence Represents a Turning Point for Justice in Guatemala

By Louise Olivier

Located in Cobán, 219 kilometers north of Guatemala City, Comando Regional de Entrenamiento de Operaciones de Mantenimiento de Paz (CREOMPAZ), a former military base, was closed in 2004. Known as Military Zone 21, in 2012 it was the site of a shocking discovery—one of the largest mass graves ever unearthed in Latin America.

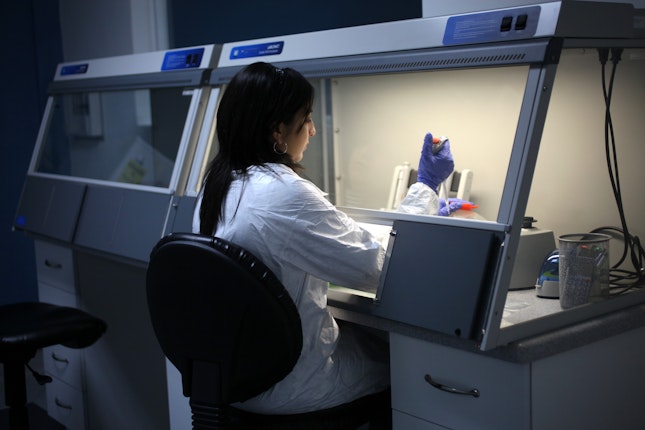

The discovery, and the criminal charges that followed, became widely known as the CREOMPAZ case, and may prove to be a watershed moment in accountability for grave crimes. It led to a two-year forensic investigation by the Guatemalan Forensic Anthropology Foundation (FAFG), which investigates and uncovers evidence of human rights violations committed during the country’s civil war. The foundation also assists the justice system with forensic evidence for prosecutions, identifies the victims of these crimes, and assists the victims’ families in recovering their remains.

The CREOMPAZ case brought to light some of the worst state-perpetrated atrocities of the Guatemalan conflict. At the request of the public prosecutor’s office, the foundation's forensic experts dug for, recorded, and exhumed the remains of 558 people, including 90 children, in 84 mass and individual graves.

To date, DNA testing has identified 97 victims from all over Guatemala using the National Genetic Database for Families and Victims of Enforced Disappearances. Many of the bodies were blindfolded and their hands and feet bound, suggesting that the base was used as a clandestine interrogation and detention center—and that its victims were summarily executed.

On January 6, the public prosecutor’s office ordered the arrest of 18 retired military officers for war crimes allegedly committed during the country’s 36-year internal armed conflict, which took place from 1960 to 1996 and claimed 200,000 lives. Fourteen of those arrested are charged with enforced disappearance, murder, and torture as crimes against humanity.

The forensic evidence gathered by the foundation has allowed the public prosecutor’s office to corroborate eyewitness testimony of the abductions and killings that happened at Military Zone 21. The remains that were found were of ordinary people who one day kissed their loved ones goodbye and left for school, college, or work and never came home. Most people who disappeared were poor, came from indigenous communities, and were branded as “subversives” by the state.

According to the foundation, military and state documents show that the state considered the unarmed civilian population an internal enemy, which led to systematic and generalized attacks by state security forces and paramilitary groups against political opposition parties, unions, priests, lawyers, journalists, professors and teachers, peasants, and indigenous people.

Should the recent arrests result in criminal prosecutions, the CREOMPAZ case has the potential to prove the critical role of forensic physical evidence in seeking justice and accountability for grave crimes. Yet Guatemala has before been at the cusp of setting meaningful precedent on holding those responsible for grave crimes accountable, and ultimately failed to do so.

In 2013, former president Efraín Ríos Montt was tried and convicted in a separate case of genocide and crimes against humanity, but the verdict was overturned just 10 days later and a retrial is still pending. A number of related trials are keeping such atrocities fresh in the minds of Guatemalans.

The CREOMPAZ case is full of tragicomic contradictions. The site of the atrocities is now a regional training center for United Nations peacekeeping operations. Instead of being commended for their work, the foundation’s staff are vilified in the media by state apologists and conservative entities, such as the Fundación Contra el Terrorismo, which targeted the foundation in advertisements and newspaper articles.

Perhaps most fantastically of all, many of the officers now implicated are intimately connected to the National Convergence Front (FCN–Nación), the political party founded by retired military officers that brought comic actor Jimmy Morales to victory in last year’s elections. Some of those arrested were expected to serve in Morales’s cabinet.

On January 14, just eight days after the CREOMPAZ arrests, Morales took office as president. Now, his presidency may well be defined by the most important anti-impunity efforts in Guatemala’s history—efforts that could set a standard for the rest of Latin America, or continue the farce that has left the victims’ families without the justice they so desperately seek.

Louise Olivier is a program manager with the Open Society Human Rights Initiative.