In German Schools, a Quiet but Deep Discrimination Problem

By Zsolt Bobis

Just over a month ago, an administrative judge in Berlin considered a complaint filed by three young German students over alleged racial discrimination at school. All three were from what Germans call a “migrant background”; their families were first generation immigrants. The three did not get a sympathetic hearing. The judge rejected the complaint, which the local district mayor had already dismissed in a local newspaper as the “year’s craziest law suit.” Conservative media reports were equally disparaging; for them, apparently, this was a case of three migrant children trying to play the racism card to excuse their own academic failure.

The three students and their families are, of course, not alone—although distinguished by having the courage to take a stand over their experiences.

Testimonies of students, parents and teachers, recounted in a new photo report by the Open Society Justice Initiative, paint a bleak picture of the challenges facing children from “migration background” in Berlin who want to have the same opportunities for education as everyone else.

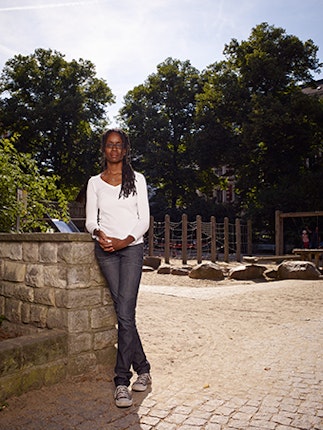

“Berlin schools have a racism problem. But the word ‘racism’ triggers such strong emotional reactions that these kinds of problems are rarely discussed, let alone resolved,” says Sharon Otoo, a black author and mother of four. According to Gülten Alagöz, a teacher and member of district council in Tempelhof, “people are quite aware of [discrimination in Berlin schools]. The problem is that no one talks about it in public.”

It is always a challenge for individuals who experience discrimination to prove that what happened to them was not just personal, something that happened because they were somehow not good enough. There is a challenge for those in the majority too: no one, or at least almost no one, likes to be accused of discrimination or racism. But sometimes discrimination or racism can be ingrained in an ostensibly merit-based system which maintains longstanding implicit practices, in which the system doesn’t recognize that minorities need support to level the playing field with the established majority.

How do we know then that discrimination exists? We look at the data.

The first official indications of a systemic problem in the German education system emerged as early as 2001 when an influential PISA study highlighted that at-risk students—including those of “migration or migrant backgrounds”—performed worse in Germany than in other comparable countries. They were more often segregated into lower level classes and schools, effectively depriving them of the opportunity to pass the Abitur examination needed for university-level education.

Even though a number of reforms have been undertaken since, the facts show there is a long way to go. As recently as in 2010, a federal Ministry of Education report noted that children with a “migration background” were twice as likely to attend a vocational secondary school (that leads to no Abitur) as children without a “migration background”—even within the same socio-economic class. In Berlin itself, for students who come from families whose original language is not German, less than a third leave with a university entrance qualification (compared to half of the state’s native German students), and in 2012 the government of Berlin reported that twice as many children with a “migrant background” were relegated from the city’s elite Gymnasium schools to the lower level Sekundarschule as native German children.

Unfortunately, reforms in themselves will not make much of a difference when school administrators and parents can still remain wedded to practices that effectively consign the majority of students with a “migrant background” to a second-class education. Based on the testimonies of teachers, including majority German teachers, German language skills and religious instruction in school are often used as a proxy to segregate migrant children into separate classes and enable school officials to lure native German parents with “German language Guarantee classes.” A recommendation for higher education in the case of students from “migration background” will often be put in doubt against the premise: “The child comes from a family not invested in education”—a peculiar observation in a meritocracy.

The German government’s failure to secure equal educational opportunity for students with a “migration background” is a violation of international and federal law, and it should be challenged. But it is always hard for parents and students to challenge a school system, which retains control over their future. Any kind of formal protest risks making your children stand out from the crowd as trouble makers; it takes time to secure remedies, by which time the child has grown up or moved on to another school.

It is time for a fundamental change in the way children are educated and supported in the classroom in Berlin in particular and in Germany as a whole. That change, among other things, requires a meaningful avenue for families to challenge the discrimination they experience in schools. That change begins with listening.

Listening to parents like Didem Yüksel talking about the experiences of her family: “I could understand this happening to me when I was in school. We were the first ones. But not to my child. This can’t still be an issue for the next generation.”

Until September 2021, Zsolt Bobis was a senior associate policy officer with the Open Society Justice Initiative.