A Victory for the Truth about Mexico’s “Dirty War”

By Mariana Mas Minetti

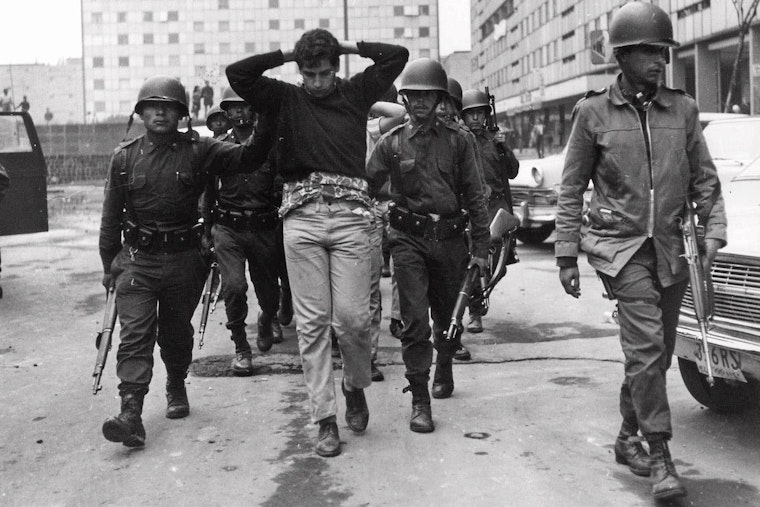

From 1968 to 1982, more than 1,200 people disappeared without a trace during Mexico’s “Dirty War.” Outside the country, the conflict remains less well known than the Cold War repression seen elsewhere in Latin America. But Mexico’s conflict was equally brutal, with the army fighting left-wing insurgents in rural areas, while the forces of the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party sought to subdue dissent in the cities through arrests, torture, and killings.

Today, the Dirty War remains a contested part of Mexico’s recent history that some would prefer to forget—given the continued influence of the Mexican armed forces, and of a new generation of Institutional Revolutionary Party leaders. But now a ruling from the country’s Supreme Court of Justice has given an important boost to those who want a proper accounting for the conflict, and its violence.

As elsewhere in Latin America, this effort has included victims’ families, who have tried to find out what happened to their loved ones. In Mexico, they have largely been met with denials; these denials have been made easier by the fact that there were at the time of the crimes systematic attempts to erase any record that the disappeared person ever existed, by destroying official records such as birth certificates and school certificates.

During the years of the conflict, some local prosecutors did launch some investigations into reported disappearances. But all ended without any charges being filed, and with the investigative files and even the names of the victims being kept secret by the federal prosecutor’s office, the Procuraduría General de la República (PGR).

As part of this effort, a request was filed under Mexico’s progressive access to information law, seeking the most basic data—the names of all those listed as disappeared by the government. This effort was initially blocked by the PGR, which refused to release the relevant 135 files, a decision that was then supported by the National Institute of Access to Information and Persona Data, which oversees the application of the access to information law.

The Open Society Justice Initiative, along with Litiga OLE, a local legal group focused on human rights litigation, then filed a constitutional challenge to this decision with the Supreme Court (an amparo) on the grounds that the access to information law, which came into force in 2003, includes a “human rights override,” which says government agencies cannot withhold information related to investigations of human rights abuses or crimes against humanity. The amparo also cited the collective aspect of the right to truth, the right to the recognition of legal personality, and the right to a name for the victims, which must be proportionally weighed in cases on forced disappearances.

The result was a ruling of the Mexican Supreme Court of Justice on February 1 that granted the petitioners’ right to gain access to the names, on the grounds that the information requested cannot be kept classified when it refers to crimes constituting grave human rights violations, which include forced disappearances. This court ordered the National Institute of Access to Information and Persona Data to issue a new resolution and to order the PGR to disclose the requested information to the claimant, and allowed the claimant to make those names public.

The decision was immediately welcomed by the Mexican chapter of HIJOS, a group which campaigns for the victims of forced disappearances across Latin America, and which hailed this important step forwards in the effort to ensure that what happened during the Dirty War is never forgotten.

But this ruling has implications that go beyond Mexico. Other countries in Latin America have similarly fraught political struggles over the question of accountability for grave crimes. Some also have similar but as yet untested “human rights override” provisions in relatively new access to information laws (most were passed in response to earlier government failures to investigate abuses committed in the name of national security in the 1970s and ’80s).

The ruling from Mexico’s Supreme Court has now established an important marker, setting out arguments that others can now use when seeking information on grave crimes and human rights abuses from their national governments. It also marks another step forwards for the right to truth, an area of developing human rights law where Latin America—because of its troubled history—has been in the vanguard.

The right to truth is defined by the UN Human Rights Council as the right of victims of crimes and abuses, their families, and society “to know the truth regarding such violations to the fullest extent practicable, in particular the identity of the perpetrators, the causes and facts of such violations, and the circumstances under which they occurred.” And why? Because knowing the truth about our past hopefully means that we will not repeat its mistakes.

Mariana Mas is a policy officer for freedom of information and expression with the Open Society Justice Initiative.