9/11 at 10: Where Were You on That Day?

By Wajahat Ali

The National Security and Human Rights Campaign at the Open Society Foundations supports organizations that are working to protect civil liberties in post-9/11 America and to promote national security policies that respect human rights. On the tenth anniversary of the terrorist attacks of 9/11, contributing Campaign grantees offer reflections on their work in this series 9/11 at 10.

Everyone has a story of that fateful day. The day of crisis and inexplicable violence has been seared permanently into the global consciousness.

The collateral damage of that tragedy not only affected the loved ones of the 3,000 innocent souls who lost their lives, but also defined an entire generation that inherited its reverberating, burdensome trauma.

On 9/11/01, I was a naïve, well-intentioned, 20-year-old senior at U.C. Berkeley sitting in my pajamas on my couch in shock, praying for the victims, and convinced what I was witnessing on the screen was just a sick joke or some Hollywood special effects.

And then the second plane hit.

As a Muslim Pakistani American, I did the “minority prayer” that all minority groups perform in moments of national crisis—I prayed the criminal terrorist was an average white guy and not a member of our tribe. When a white guy does a crime, no one gets scapegoated; it’s just a lone, crazed individual. When a minority does it, the net of collective blame is cast.

And then the faces and names of the architects of terror were revealed, and they weren’t white, but instead Muslim and Arab.

I closed my eyes, took a deep breath, and knew the next ten years would be difficult and demand tremendously hard work for “us” to prove that we, too, were American and not like “them.”

However, I realized this moment of crisis was also an opportunity for reflection and growth. By proactively telling our stories, which were often lost in the fog of sensationalism and hysteria, perhaps we could ease the inevitable divides carved by ignorance and misinformation?

That year, I was lucky to be accepted into Professor Ishmael Reed’s Short Story Writing class. As an African American, Reed empathized with the hazing the Muslim American community endured at the hands of a media hungry for sexy sound bites and exotic caricatures. Recalling similar experiences of minority communities in America’s past, Prof. Reed said the only way to dispel negative stereotypes and introduce honest, authentic narratives that reflect the true diversity of our communities is to write stories. Stories and art have the power to heal and initiate much-needed conversations that otherwise become lost in the heated rhetoric of politics and religion. Not only do they help reframe the conversation, but they are also a powerfully effective form of diplomacy for achieving mutual understanding and reconciliation.

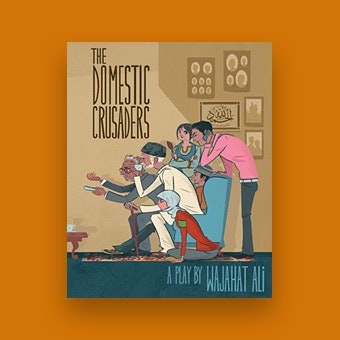

And so, in the aftermath of a tragedy, I wrote a story. What started out as a short assignment for class evolved into a full-length play, The Domestic Crusaders, which presents a universal tale through a culturally-specific lens, focusing on three generations of a Muslim Pakistani American family living in a post 9/11 world. These "crusaders" include a retired Pakistani army grandfather, his successful immigrant son and his wife, and their three American-born children. They are neither avatars of Armageddon nor of perfection, but instead messy, complicated, funny, irritable, honorable, and flawed human beings simply trying their best to assert their individuality while maintaining the unifying, but fraying, thread that is family.

The Domestic Crusaders is one of three plays headlining The 9/11 Performance Project in New York City this weekend at John Jay College’s Gerald W. Lynch Theater. This art festival seeks to confound the tawdry stereotypes and cardboard caricatures of the past ten years and present works of art intended to inspire, provoke, challenge, and revise the collective story that has, sadly, left many communities either marginalized or silenced or sensationalized and exploited.

A decade after 9/11, we still live in the shadows of the towers, futilely assuming we can escape their looming presence on our lives without confronting the simmering questions that still haunt us. Questions regarding national security, civil liberties, foreign policy, the “American” identity, and relations with our neighbors both at home and abroad – especially those with multisyllabic last names and Muslim backgrounds – remain unanswered and heated. The 9/11 Performance Project offers several panels featuring leading experts on civil liberties, law, media, and the arts to discuss these topics with an engaged audience.

Historically, stories have provided a safe space to reflect, dissect, interpret, challenge, discover, and initiate discussions on topics that otherwise either get swept under the debris or privately whispered for fear of confrontation or controversy. In both Western and Islamic cultures, storytelling has an exalted position. In seventh century Arabia the storyteller was valued more than the swordsman; he was entrusted to relate the histories, morals and values of the tribe using his artistic gift of poetry.

It is precisely with that intention we have all decided to reflect on the history of that tragic day through art and dialogue. Only then can we feel catharsis and release, which never comes by inaction and silence.

Over the course of the weekend, a few toes might be stepped on, and there might be a hearty disagreement or two, but this will be well earned because art, shared stories, and challenging conversations allow us to move beyond ignorance, pain, anger, hysteria, extremism and separatism, and inspire us toward remembrance, reconciliation, resilience, and resolve.

Wajahat Ali is an attorney and the author of the play The Domestic Crusaders.