Building the Civil Society of Tomorrow Means Investing in Teachers Today

By Trine Petersen

This World Teachers’ Day, October 5, it’s time to consider how support for professional teachers helps them do their urgent jobs more fully.

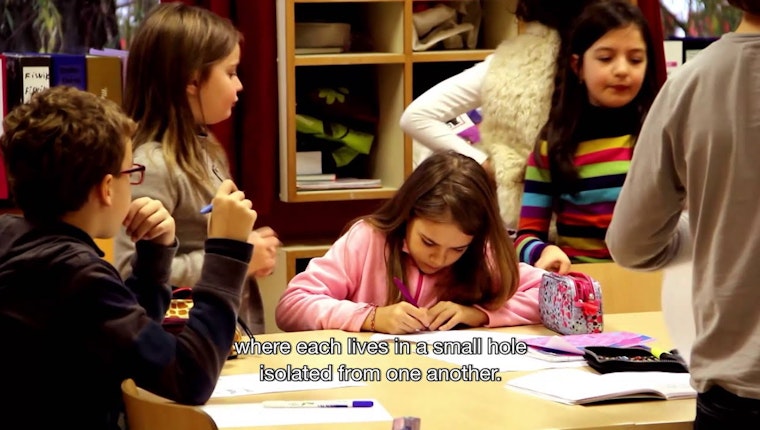

This becomes clear in the video above, produced by Education International. It shows teachers around the world aiming to exceed the rote tasks of lessons and disciplines. They work to help young people develop into confident, responsible citizens despite adverse circumstances. “As teachers we must always be able to promise something better than what society offers,” says David De Coster, a teacher. His vision of quality education shows how a commitment to open society, for many children, starts with a good teacher.

And do not doubt that enlisting teachers as civic leaders can help address the global learning crisis. An estimated 250 million children around the world—many of them from disadvantaged backgrounds—are not learning basic literacy and numeracy skills, let alone the further skills essential for social, political, and economic participation. Estimates peg the cost of this skills gap at $129 billion, but there is also an incalculable cost to societies.

So why should we think that supporting teachers, rather than demanding more from them, will help reverse these costs? Substantial research on the link between teacher characteristics and student learning shows that education quality rises with support for teachers, and deteriorates when teachers lack support. One significant element in solving the learning crisis is ensuring that all children have teachers who are trained, motivated, and connected; who enjoy teaching; and who can provide differentiated support within functioning school systems.

A lack of people and a lack of support hinder this goal. First, there is a severe shortage of teachers in many of the poorest countries, resulting in large class sizes in early grades (in some cases up to 160 learners per teacher) and in the most economically deprived areas. Analysis by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics shows that universal primary education would need an influx of over five million teachers between 2011 and 2015, with Sub-Saharan Africa accounting for 58 percent of these.

Teachers hesitate to work in areas that lack basic amenities and that are long distances away from their homes, and consequently many learners in high-need areas, who are already the most disadvantaged, suffer. This gives rise to huge disparities in achievement among learners in rural versus urban settings, for instance. Governments need to take proactive steps, like providing safe housing for women or tailoring financial incentives, to recruit teachers where learners need them most.

Second, salaries are an important factor in motivating teachers. In many low-income countries few teachers can afford basic necessities without taking a second job. In Central Africa, Liberia, and Guinea-Bissau, teachers are paid $5 a day. Such poverty wages repel recruits and drive current teachers away. They also prevent a robust education system, with teacher training, from growing.

Third, teachers need training in how to teach in classrooms before they start a job. This rarely happens. The case of Ms. Sharma in the video highlights one workaround that countries use: hiring contract teachers who have not studied the profession. Current global development frameworks’ focus on rapid expansion of education provision have led some governments to roll out schools without the necessary infrastructure to prepare teachers.

This lack of training reinforces the “talk and chalk” approaches, which do little to foster critical thinking and independent inquiry. These challenges need addressing through curriculum development and teacher training.

Instead, too many nations ride on global trends in education reform that favor standardization across systems, often with a narrow focus on a few subjects (usually math, reading, and science), and a significant emphasis on testing of students. As the instructor De Coster says, teachers are sometimes seen as a “market good,” although studies have shown that an emphasis on testing sometimes narrows curriculum focus and favors mechanistic instruction over more sophisticated pedagogical approaches. It also feeds a sense of de-professionalization of teachers, which hurts teacher recruitment and retention.

These vicious cycles show why the current discussion on the post-2015 development agenda is so important. The current proposed goals, which are now being negotiated, contain specific language calling for countries to secure teacher recruitment, training, and motivation in order to “ensure equitable and inclusive quality education and lifelong learning for all by 2030.” These are crucial if we want every learner to contribute positively to society.

Education International is a grantee of the Open Society Foundations.

Until April 2015, Trine Petersen was a program officer for the Education Support Program.