Clearing a Path to Justice in Nigeria

By Chuck Leung

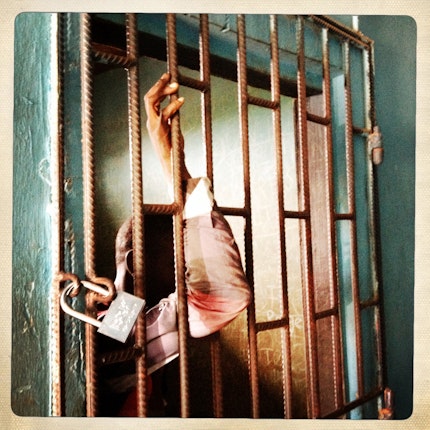

In Nigeria, nearly 70 percent of prisoners have not been convicted; detainees spend an average of over three years awaiting trial. To help fight this, the Open Society Justice Initiative has supported a project that sends young lawyers into police stations, working to process cases quickly. We spoke with photographer Benedicte Kurzen, who visited the city of Akure to document the efforts, also posting images to Open Society’s Instagram account.

What are some of the obstacles detainees face in their attempts to access legal assistance?

In Akure, as far as I understand, a solicitor is not available in all police stations. To make sure this practice leaves as few people behind as possible, more solicitors are needed.

The lack of resources available for those solicitors to do their work needs to be addressed, in order to enable them to do their job in the most efficient way. Barrister Kubiat, who has served for nine years and is head of the Legal Aid Council in Ondo State, doesn’t have a large enough salary to buy a car, for instance.

Meanwhile, from the police officers’ point of view, there is still some resistance to the project, perhaps due to feeling as if they are suspected of corruption.

Can you describe the interactions between the detainees, solicitors, and law enforcement you observed, and what was unique about them?

It is a fragile balance of give and take. In large part, the solicitors basically serve as a public service to the poor but also have a real filtering role by preventing suspects of petty crimes from being sent to court or jail, which helps the already overwhelmed, overcrowded criminal justice system.

Moreover, the solicitors seem to work closely with the police, which allows them to meet, interview, and negotiate the release of some suspects. I was really impressed with the amount of diplomacy that Barrister Kubiat showed, for example, in order to keep the relations within this triangle balanced. A lot was directly connected to her warmth and politeness with others.

The quality of the project is closely linked to the trust the police build with the solicitors—hence the importance of having the same solicitor based in the same police station. This is probably key to slowly establishing in the police officers’ minds the idea that solicitors are actually facilitating their tasks. In some cases, there was a great sense of pride from both police and solicitors about this collaboration.

What’s most challenging as a photographer working in spaces like these?

The main challenges were related to the culture and the general suspicion that the presence of a camera raises in such a space. This made the window of opportunity tight, and the work needed to be done as fast as possible, in a “one-hit” sort of mode.

We had access to four police stations. After visiting these, I raised in the following days the idea that we should maybe go back to follow up with some cases, or get access to other offices, like the department where all the detention registries are stored.

The duty solicitors explained to me that to go back would raise suspicion, as the police might then think that our purpose was to investigate the way that they are treating suspects.

What effect do you think mobile devices or mobile photography can have on the relationship between citizen and state? Or as potential tools in service of justice?

This was my first experience using Instagram for a single subject. It was very strange to realize that most of the comments on the posts had nothing to do with the actual story. So my first conclusion was that instead of getting a committed, narrow audience, we have a wide, mildly involved or indifferent one, which is image-driven and not issue-driven.

Nonetheless, the democratization of the act of photography could be a great tool to support civil society, in terms of collecting evidence and supporting projects. Along with the actual practice, the platforms that are available to share those pictures definitely allow people to reach a broader audience.

There is huge potential, but it needs to be framed. To the question of whether mobile photography could be a tool to put pressure on the government to be more accountable, I would say it depends on the government, on the culture, on the country. An ethical approach is really the key here.

I also think we are only starting to understand how mobile photography can influence our interaction with the world. It is really a difficult question. I don’t think we quite know where it will go. As the French philosopher Virilio said: Every form of technical progress comes with its load of both positive and negative changes.

The invention of the car was also the invention of road accidents. In the context of mobile photography, I feel we are still very much evolving, and we have to keep questioning the tools we are using and the way we use them.

Until November 2021, Chuck Leung was video producer for the Open Society Foundations.