Do Gender Quotas in Politics Work?

By Aleksandra Niżyńska & Małgorzata Druciarek

The right to vote was given to Polish women in 1918 when Poland regained sovereignty after the First World War. This was a huge success for the Polish suffrage movement (consider France only allowed female suffrage in 1944) which had convinced politicians that for democracy to prosper, women must be equal partners in rebuilding the country. Ninety years after this triumph, after women’s engagement in World War II and the fight for freedom under the communist regime, the question of women’s participation in the electoral process has come up again in public debate.

In 2009, the Polish Women’s Congress gathered thousands of women to share their discontent over the underrepresentation of women in Polish politics. They proposed an introduction of parity on electoral lists, guaranteeing half of all positions to women. At that time female MPs constituted only one fifth of the Polish Lower House of Parliament (Sejm) and no more than 15 percent of its Upper House (Senat). It was far below the expectations of Polish society, which supported the idea of bringing women’s voices into public debate.

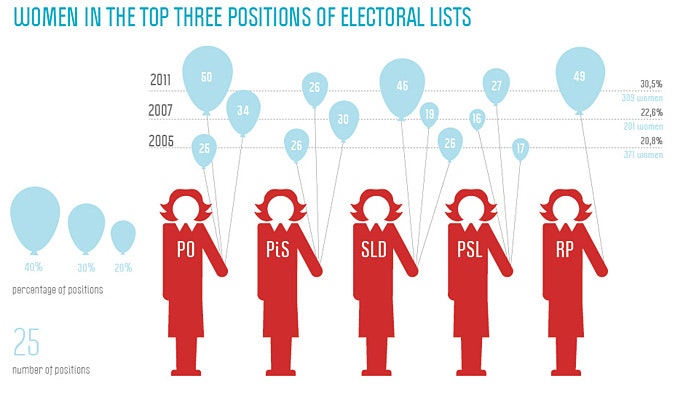

After a series of political games and parliamentary intrigues, the desired parity (50 percent of female and male candidates) did not happen. Nevertheless the idea of equalizing political chances for women and men as electoral candidates remained important for women’s NGOs. Thanks to their determination and political skills, a 35 percent gender quota was introduced. The new Electoral Code of 2011 guaranteed both women and men at least 35 percent of positions on the electoral lists. If an electoral committee did not fulfill this requirement, the list would not be registered. The sanction turned out to be effective, since the number of female candidates to the Lower House of Parliament doubled in comparison to previous elections in 2007, exceeding 40 percent of positions on all electoral lists. However, the electoral result of women in 2011 was not as impressive. Currently, almost one quarter of all MPs of the Lower House of Parliament are female politicians. This means that the increase of women in Sejm amounted to only 4 percentage points since the last elections in 2007.

Does this mean that gender quotas do not work? Why were they not effective in the Polish case, while they proved useful in other countries such as Kyrgyzstan, Serbia, or Belgium? We believe the fault lies with the lack of rank placement requirements in the Polish electoral system. Rank place requirements mean that certain positions on the electoral lists are reserved for women. It can be, for example, one in the first three positions on the list or two in each consequent five positions on the list. One of the most popular types of rank place requirements is the zipper system. According to our research—both qualitative and quantitative—presence on the electoral list is just the first step in a long journey to Parliament. In the case of Poland the crucial factor appears to be the position of the candidate on the physical list itself. Political parties know many methods of placing women on the electoral lists without giving them any real chance of winning. The most obvious ploy is to reserve places at the very end of the list for women. It is commonly known that voters more frequently cast their vote for the candidates positioned at the higher end of the list. Featuring in the first five positions on the electoral list increases one’s chances in the electoral race to a noticeable extent.

However, even if someone is placed at the top of the list, it does not mean a secure place in the Parliament. One might be the leader of the party list in a district, where the electorate is negatively oriented towards a particular political party. In Poland, eastern regions are traditionally more conservative and more often choose right-wing parties compared to western parts of the country. This means that being the female leader of the Left in the East of Poland—so appearing at the top of the electoral list—is much more disadvantageous than having fifth or sixth position on the list in western districts. In this case, we might speak about “winnable” and “unwinnable” places, which are estimated according to the result of the specific party in the specific district in the previous elections.

Nevertheless, even if women get the “winnable” position it does not mean that their chances of election are equal to male candidates. Within the frame of our research project we carried out a media analysis of TV electoral campaigns. Among all candidates presented during free air time in public television before the elections only 27 percent were women. This appears to be the tip of the iceberg. Female candidates are put on stage much less often during the electoral campaign, which makes their chance of being elected much weaker. Even if women do appear on TV spots or on billboards, their image tends to be constructed on the basis of being a good manager of a household budget, while male candidates are presented as managers of national finances. The message is clear—men are suitable for politics and women for housekeeping.

Taking into considerations all of these obstacles to winning elections which female candidates endure, their electoral results begin to look much better. Women gained almost one quarter of all seats in the Lower House of Parliament, which is the best result in the history of Polish democracy. It must be admitted however, that if not for the policy of quasi-soft quotas, initiated by the political party Civic Platform, this number would probably be lower. The party, which is now governing together with the Polish People’s Party, decided to put at least one woman among the first three positions on the list and at least two among the first five. In effect the percentage of female Civic Platform MP in the Lower House of Parliament amounts to 35 percent, which exceeds the so-called critical mass—the percentage of a minority in any group which gives the minority a chance to take part in decision-making process. This example may be a good argument in favour of introducing a zipper system, where female and male candidates are placed in alternate slots among the top ten positions on a party’s candidate list.

Unfortunately the zipper system cannot be used in other types of parliamentary elections, namely the ones to the Upper House of Parliament. Parallel to the process of introducing quotas and enabling men and women to be equally represented in the Lower Chamber, the Polish legislator ordained that elections to the Upper Chamber would be organized according to a majority system. This means that from each electoral district each committee may put up just one candidate. Taking into consideration overall attitude of political parties towards women, the chances for them to run for office are very low. In 2011 only 14 percent of all candidates aspiring to the senator seat were female. As a result, in the Upper House of Parliament only 13 women were seated, which is equivalent to 13 percent (in the Polish parliament 100 senators take seat).

If we want to answer the question: “do quotas in politics work?” we need to think about specific conditions around their introduction, the political climate, and the cultural background of the country including the position of women in a society. The lesson that can be learned from the Polish experience is that implementation of gender quotas has to be accompanied with many additional mechanisms that will make them practically effective. These include the zipper system or placing female and male candidates in alternate slots among the top ten positions on a party’s candidate list.

Above all, we need to remember that the majority electoral system will diminish the positive effects of equalizing mechanisms in politics, because this system affords the opportunity for office to a very limited number of people. It remains that women have significantly less chance of becoming a candidate in the majority systems. Gender quotas don’t always work, but they remain a useful tool amongst one of many that will bring gender parity to political decision-making institutions.

Aleksandra Niżyńska is a project coordinator and researcher with the Law and Democratic Institutions Program at the Institute of Public Affairs in Poland.

Małgorzata Druciarek is a project coordinator and researcher with the Law and Democratic Institutions Programme at the Institute of Public Affairs.