Documenting the Human Cost of U.S. Immigration Policy

By Chuck Leung

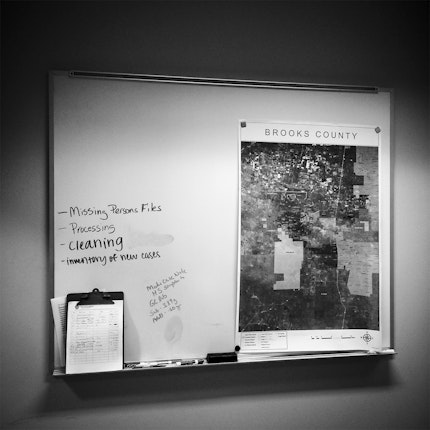

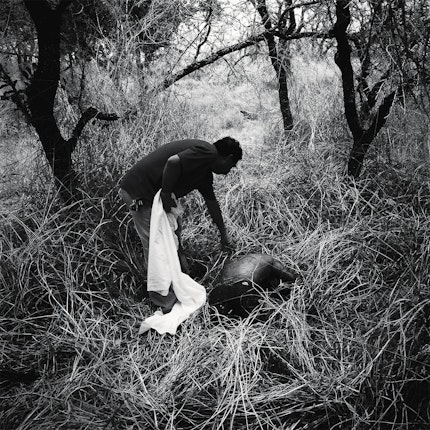

In the parched ranch land of Brooks County, just north of the Texas–Mexico border, the remains of over 250 migrants have been discovered since 2012. Photographer Brandon Thibodeaux recently visited the region to document the growing human cost of U.S. immigration policy, also posting images to Open Society’s Instagram account. He spoke to us about his work.

What inspired you to address some of these unseen aspects of the migrant experience in this region?

I live in Texas, I was born here, and people are dying in my own backyard. That, in and of itself, is enough. In 2013 the Wall Street Journal and I produced a piece about the number of migrant deaths occurring in south Texas. This recent trip was an attempt to further explore the issue and to pick up where that piece left off.

There’s been so much recent debate around immigration reform. From your perspective, what’s being left out of the discussion? What do we misunderstand?

When you live in Texas, immigration is never far off your radar. We live with it in nearly every aspect of our lives. Unfortunately, the left–right political paradigm muddles the debate so much that there is very little room left for considering the humanity of it.

When a mother chooses one of her three children to take with her to the United States, based on its size and how much it will cost to feed it, that amount of desperation and mental certitude will overcome any barrier, no matter how tall you choose to build it. What man or woman, son or daughter, would risk their lives to leave their home and family if they had a choice? These people aren’t coming because we live in the Promised Land but because the promise for their land can no longer be seen. I think what we misunderstand is ourselves.

The centuries of one-sided foreign policy that Latin American countries have been subjected to for the advantage of the developed world are the root cause for the civil and economic unrest that these people are fleeing. Until we take responsibility for our role and work to address the root cause of immigration, the debate will always be one of reactionary measures. And in the meantime people will still be dying in our deserts.

What do you think of the connection between social media and activism?

Social media is the digital embodiment of human consciousness; I’d argue that it’s likely where most young folks get the bulk of their day’s information. It seems appropriate that it be used for activism. One only needs to look at the Arab Spring for an example of its potential. Whether that power is harnessed and used in an effective and enduring way is the real question.

There was an interesting discussion in the comments of one of your posts about what documentary photojournalism is, or what it should be. What are your thoughts, at least in this particular context? How much does the medium matter?

Instagram estimates that 60 million photos are published on its platform each day. What I find to be most interesting is that people are debating the semantics of photojournalism on Instagram. Despite the overwhelming number of visuals being created and devoured, photojournalism and the respect and trust it garnered in the 20th century has survived in the minds of folks.

We as photographers, be it photojournalism or visual narrators of any sort, are the torch-bearers for one of humanity’s oldest traits—aside from killing, eating, and reproducing: We tell stories. From the hand pigmented cave dwellings of France to the digital interface of an Instagram feed, our delivery methods may have changed but our desire to tell or to be told an effective story has remained constant.

By seeing and trying to understand, we share what it means to be alive and the challenges of our time. However, the viewer’s reaction to a photograph is still subjective, so the best we can do is stay true to our own means of expression—maybe even more so today than ever.

Until November 2021, Chuck Leung was video producer for the Open Society Foundations.