Exiled to Nowhere: Burma’s Rohingya

By Heather Marciniec

The Rohingya are from western Burma. As a Muslim minority group, they face systematic discrimination by the military regime. An outbreak of severe violence in the western Burmese state of Rakhine has refocused international and regional attention on the issue of the area’s estimated 800,000 stateless Muslim Rohingya threatening to destabilize the country’s wider transition away from military rule. The government declared martial law in Rakhine recently after an escalation of violence involving local Buddhist and Muslim communities that resulted in an unknown number of deaths and the burning of hundreds of homes. The Burmese government, including the military, police and local security forces, has responded with violence including mass arrests and the reported use of torture against the Rohingya population.

Tensions in the region, which borders Bangladesh, have historically been fueled by Burma’s denial of citizenship to the Rohingya who are also not recognized as one of the country’s official ethnic nationalities. Greg Constantine, a grantee of the Open Society Foundations, has spent the past several years documenting the plight of the Rohingya and believes their story is one of the most forgotten, neglected and worst cases of human rights abuse in Asia today. I had a chance to talk with him about his new book, Exiled to Nowhere: Burma's Rohingya.

Q: Congratulations on your new book. Why did you decide to write a book about the Rohingya?

For the past six and a half years I've been working on a long-term project called Nowhere People. The project documents ethnic groups around the world who have had their citizenship stripped or denied from them and they are now stateless. As a result, they belong to no country, are denied most rights, and are some of the most vulnerable people in the world.

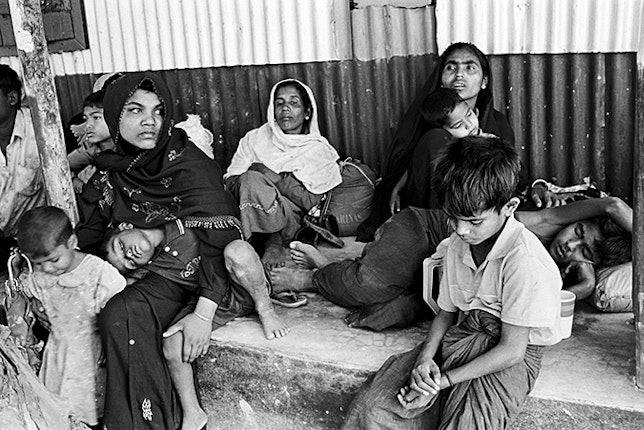

One of the most extreme cases of statelessness in the world involves the Rohingya from Burma. I've spent the most time photographing them over the past six years primarily because I truly believe their story is one of the most forgotten, neglected, and worst cases of human rights abuse in Asia today. My project and the book it resulted in, Exiled To Nowhere: Burma's Rohingya, aim not only to show the neglect and exploitation the Rohingya face as both recognized and unrecognized refugees in Bangladesh, but it also to demonstrate the abuses they endure in Burma.

From my first trip in 2006 to my most recent trip in early 2012, Rohingya have shared amazing stories with me that, when woven together, create this narrative that I've always felt people need to see and understand. A handful of photos published here or there just doesn't do the Rohingya's story justice. I've always envisioned my work and their testimonies in book form as the most effective way to tell their collective story.

Q: Who are the Rohingya?

The Rohingya are a Muslim minority who have lived in the Arakan (or Rakhine) State of western Burma for generations. While Burma and Rakhine are predominantly Buddhist, the Rohingya have been the minority in Rakhine and their connection to Burma has been challenged and manipulated by successive Burmese governments. It's estimated that some 800,000 Rohingya live in the townships of North Rakhine, which is an area that is totally off limits to journalists and most other people.

The legacy of persecution against the Rohingya in Burma dates back decades and there have been waves of Rohingya fleeing Burma. Currently, there are up to 300,000 Rohingya living in Bangladesh—most are not recognized as refugees—and tens of thousands living in Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, and several other countries in the region.

In Burma, Rohingya people are subjected to forced labor, land seizures, religious persecution, arbitrary taxes, and constant harassment from the Burmese security force NaSaKa. For years they have been denied the freedom to travel and have faced serious restrictions on the right to get married. They have also been denied Burmese citizenship.

Q: When did the Rohingya become stateless and why?

Though some historians say the Rohingya have lived in Burma for hundreds of years, others challenge the fact that they legitimately belong there. This is a result of politics, perceived notions of national identity, and blatant discrimination and intolerance.

It’s true that there was some migration of people into Burma under British rule, but a large Rohingya community had lived in western Burma well before then.

Most of the problems for the Rohingya started when Ne Win, a military strongman and leader of Burma, seized power in 1962. His policies toward the Rohingya dramatically impacted the community for the next 30 years. The Burmese government consequently enacted the 1982 Burma Citizenship Law. The law provides “full” citizenship to those from Burma's 135 recognized “national races.” The Rohingya are not listed as one of these “national races” and as a result some 800,000 Rohingya have become stateless.

Q: Have they benefited from the recent reforms in Burma?

I don't think the Rohingya in Rakhine State have benefited at all from the new reforms, certainly not the Rohingya who live in North Rakhine State. But then again, in these times of euphoria over Burma, we have yet to see who will actually benefit from the reforms. Yangon is one thing, but it’s different for the millions of people who live in Burma's countryside or border regions.

The lives of most Rohingya are still tightly monitored and controlled by the Burmese security force NaSaKa. Rohingya in North Rakhine State still face severe restrictions on the right to get married—Rohingya wishing to get married must receive formal permission from NaSaKa first.

Many of the abuses the Rohingya are subjected to on a day-to-day basis are totally invisible to the international community. They haven't come in the form of violence or killing. These brutal administrative tactics make life so miserable and untenable for the Rohingya that many find they have no choice but to leave Burma in order to live—with dignity and a “normal” life. Rohingya will tell you that all the tactics of the Burmese authorities are motivated by one thing: to force the Rohingya into Bangladesh.

Q: How are the Rohingya different from or similar to other stateless populations around the world?

I think that one of the biggest differences I've seen between the Rohingya and other stateless communities around the world is that many people feel very little hope—at least right now—that their situation will improve in the near future. All the international players—Western governments, ASEAN nations, the United Nations and others—know how serious the situation is but have done little or nothing to improve it.

Q: How were you able to capture the life experiences of so many Rohingya?

I started photographing the Rohingya community in Bangladesh in early 2006 and have made eight trips in total. My last trip was in February 2012. Their situation is fluid, it changes nearly every year, and I've tried my best to chronicle this.

Each visit allowed me the opportunity to better understand their community and the complexities of their situation. Each visit provided some new piece to the puzzle and with each trip the network of people I met and situations they permitted me to photograph developed. As I’ve learned more about the Rohnigya community, their situation and their history, I’ve also learned what I want to capture in my photographs and what questions I want to ask them. One of my main objectives has been to use their stories and my work to show the abuse the Rohingya face in Burma.

Traveling to North Rakhine State is pretty much impossible for journalists—or anyone else for that matter. And even if I had managed to get there, getting access to Rohingya there and being able to talk honestly with them and take photographs would put their safety at great risk. Rohingya are constantly fleeing Burma to Bangladesh, bringing new and up-to-date stories. In Bangladesh, they can talk freely with me.

Finally, I think it’s important to point out that the treatment the Rohingya have received in Bangladesh—from denial of humanitarian assistance to exploitation and poverty—is another huge part of their story which also needs to be told. People need to know that while the root cause of their problems rests inside Burma, their plight has no borders.

Until January 2013, Heather Marcinec was a program officer with the Open Society Burma Project/Southeast Asia Initiative.