Five Years After the Earthquake, a Public Park Unites Haiti

By Will Doig

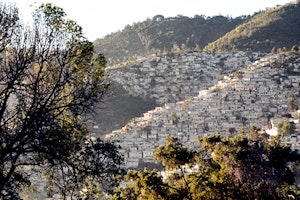

Today, five years after a devastating earthquake, the Open Society foundation in Haiti, Fondation Connaissance et Liberté (FOKAL), held a commemorative ceremony in Martissant Park, where there is a memorial for the roughly 300,000 victims of the disaster. Michèle Pierre-Louis, president of FOKAL and Haiti’s former prime minister, talks about how FOKAL spearheaded the park’s creation and its importance to the city’s development.

Where were you when the earthquake struck?

The earthquake occurred exactly two months after I left office as prime minister. I was working at FOKAL and left at three o’clock to go to my apartment. On my way there I realized I needed to go somewhere else first, and I was in that other place when the earthquake hit. I later found out that my apartment building collapsed. So it’s one of those things—in one second you change your mind about something, and if you hadn’t, you would be dead.

That night I slept on the ground under an open sky. It was a beautiful night, as a matter of fact. It was paradoxical, because people were hurt, and had lost their loved ones, yet they were singing. We were all singing and sleeping in the streets. I had lost practically everything I owned, but there was such a feeling of solidarity. This is my own experience.

Building city parks is not typical work for a foundation like FOKAL. Why is this project important?

When FOKAL was created, we worked extensively in rural areas. But Haiti was becoming more urban, and in a city like Port-au-Prince, the idea of public space in cities is not understood. It practically doesn’t exist.

And when the earthquake occurred it gave us an opportunity to get into more sophisticated issues, like how to develop a neighborhood after such a disaster. For three years we had a community dialogue where we really got the community involved in every aspect of what we were doing with the park. It was very challenging.

Can you describe what progress has been made in rebuilding Port-au-Prince since the earthquake, and how the park fits into that progress?

I don’t think it would be fair to say that nothing has been done, but after the earthquake, 60 to 70 percent of [the relief and recovery] funds went to humanitarian causes. Very little went into public construction. And in Haiti there’s a problem with lack of access to credit, which makes it hard for individuals to rebuild.

This means that the middle class was probably the sector that was hurt the most by the earthquake. Those people had built their houses with their own savings—it took them 25 years to build them, and they collapsed in 36 seconds.

When we started on Martissant Park, the idea was to see if a project like this could be a good model for the rebuilding of Port-au-Prince. Because construction takes time. A few years ago I went to New Orleans, and people were saying six years after Katrina that not enough had been done. Can you imagine how hard it is for us in Haiti? It’s a long process.

And yet against all odds, after one of the worst natural disasters in history, Haiti keeps going.

Haitians have a lot of courage, and a strong sense of resilience when facing adversity. My hope is that together we can face the challenges ahead of us. And not just Haiti. Look at what’s happened in France. It’s become a solidarity movement that’s shaken the world. In the midst of what seems to be desperation, there is still reason to believe in the common good and the public interest.

Until February 2017, Will Doig was a senior editor for the Open Society Foundations.