“I Am Kuwaiti”

By Sebastian Kohn

When Kuwait became independent in 1961 about a third of its population was granted nationality. Another third was naturalized as citizens. The rest were considered “bidoon jinsiya”—without nationality. The bidoon, as they are known, have been stateless ever since. This fall, as part of its work to end statelessness around the world, the Open Society Justice Initiative commissioned photographer Greg Constantine to document some of their stories.

You’ve had a lot of experience photographing stateless populations—including the Nubians in Kenya and the Rohingya in Burma. What were your first impressions of Kuwait and of the bidoon community?

The first thing that struck me was just the huge disparity between the Kuwaitis and the bidoon. The Kuwaiti government provides social and financial benefits to its citizens that are unlike anything I have seen before—enormous housing benefits, health benefits, almost assured employment, free education, and financial benefits for being married and for having children that would dwarf the incomes of a huge percentage of people in developing countries around the world. In Kuwait citizenship is clearly more than the right to have rights—to have a passport and be recognized and so on. It is an open door to a secure future for you and your family.

The bidoon are cut off from all of this. They live in slum-like settlements on the outskirts of urban areas. They're denied access to birth certificates and somewhere between 90,000 and 180,000 people are refused access to essential services, including health care and public education.

When you speak with them, you hear about the history that many of the families have in Kuwait, many of which pre-date Kuwait’s independence, and very quickly you see these stark differences and inequalities—inequalities that have been created and perpetuated by the state. You hear how, since the mid-1980s, the bidoon community has been almost completely excluded from Kuwait’s elite—be it political, professional, military, etc. The word “bidoon” in Arabic means “without” and it's an apt description of their situation.

As is so often the case with stateless populations, the plight of the bidoon seems to be bound up in questions of history.

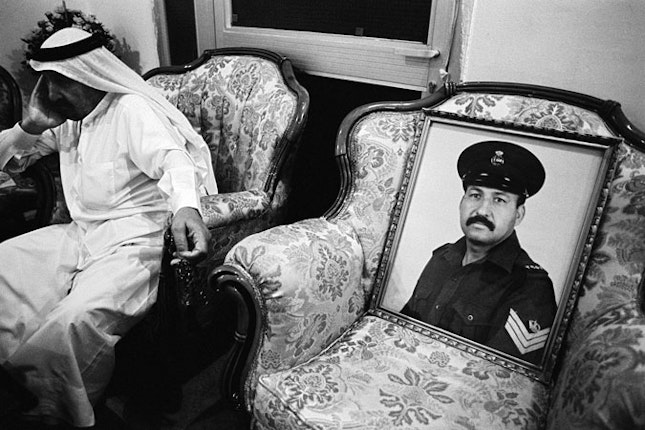

The bidoon don’t lack for history. Many families trace their history in Kuwait for generations. They point to how the bidoon made huge contributions to the development of Kuwait’s oil industry in the 1930s. They point to how the bidoon community was the backbone to Kuwait’s police and military all the way up to the Gulf War in 1991. They can show that people in the bidoon community, in so many ways, belonged—or at the time felt like they belonged—in Kuwait. The problem isn’t a lack of history. The problem is that the powers that be in Kuwait simply refuse to recognize that history. They have chosen to manipulate history in a way that has marginalized and ultimately segregated the bidoon from Kuwaiti society.

What kinds of stories did you hear? Is there a typical story or is every family different?

You could say there was a generational divide. The stories told by the older generation—the bidoon who were working age during the 1980s and during the first Gulf War—focus almost completely on government’s denial of their history. For much of the 20th century, bidoon lived side by side with others in Kuwait. They worked in the same offices, wore the same police or military uniforms, and were for the most part were treated as equals. Then, in less than 5 years—from 1986 to 1991—they were fired from their jobs, lost any rights they had enjoyed, and all of a sudden were labeled as “illegal foreigners.”

They describe the denial of the contributions by so many generations of bidoon to the development of Kuwait and its defense. They look back at the sweat they poured working in the oil fields for the British and then for the state-owned Kuwait Oil Company and all the extreme wealth Kuwait has enjoyed because of this. They describe the sacrifices they made during Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, when the bidoon were the backbone to Kuwait’s army and police force. All of that was erased in only a few years. They feel a huge sense of betrayal.

One 54-year-old man I talked with, who asked that I not use his name, traced his family in Kuwait back generations. He began his service as a technician in the Kuwait Air Force in 1977. In 1989, he received the Silver Certificate of Honor and in 1989 had received a recommendation for the Gold Certificate. He has a letter from the major of his air force unit praising him for his service in the August 2, 1990 Iraq invasion. Yet in 1991, like all of the bidoon working for the Ministry of Defense, he was fired because of “public security reasons.” Since then, he’s battled not only with ill health, because of lack of access to health care, but also with this heavy sense of shell-shock after having this fundamental element of his identity—his being a Kuwaiti—torn away for reasons he is still trying figure out.

I met him at a beach in Al-Ahmadi, the suburb of Kuwait City home to the headquarters of the Kuwait Oil Company. We talked for a while. Eventually we moved into his car because it was more private and the breeze outside was too strong from my microphone. I asked him to turn off the air conditioner in his car so I could get a better recording of him talking. As the temperature rose, he described the part of his story that was most painful—his dismissal from the air force.

“I felt shocked and also was disappointed and felt pain,” he said. “I thought, ‘Why? What did I do wrong? What crime did I commit?’ I felt like one of the essential parts of my body had been amputated. We used to live in peace with our neighbors, with our relatives and helped each other to coexist, like one happy family. But I don’t know all of a sudden what happened?”

He still carries his military ID that states his nationality is Kuwaiti, even though it is of no value to him now.

What did you hear from the younger generation?

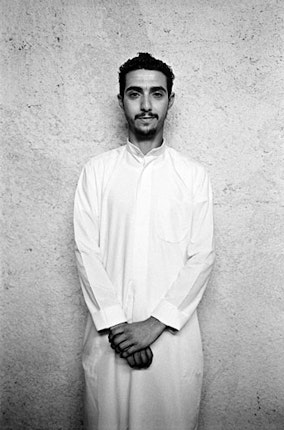

For anyone under the age of 35, the stories tend to emphasize a general sense of paralysis. They talk about the enormous inequalities they face with regard to employment, education, social benefits, and so on. Like many stateless people, they have learned to adapt and improvise, but they realize that these alternatives will never provide a sustainable future for them or their families. Nearly all of the bidoon youth I spent time with were unemployed. Many had dropped out of school because their families couldn’t bear the cost. Many are single, either because they lack the money to get married or because they feel they’re in no position to offer a future to a family.

I met one 23-year-old bidoon, Khalid, whose great-grandfather had been born in the deserts of Kuwait, before Kuwait was even a country. Khalid had gone to school, where he studied nursing. After spending thousands of dollars on his education—because he was not allowed to attend a Kuwait government university, where tuition is free—Khalid graduated. But no company would hire him because the government’s “bidoon committee,” which was created to handle all issues related to the bidoon, had restricted all employers in Kuwait from hiring bidoon. He’s now unemployed. “Myself and other young bidoon always want to think of a better future,” he told me. “But the obstacles are so dark, they don’t let us see what our future is like.”

You sought out bidoon artists, particularly poets. What role does poetry play in this story?

This was a very important part of the story. I’ve been working on statelessness for years and I know how complex an issue it is to talk about. I think this is one of the challenges for people and policy makers grappling with the problem. Just like stateless people, statelessness itself—the idea—occupies a space that’s difficult for people to define and understand.

With that in mind, I don’t think it’s a coincidence that some of the most respected poets in Kuwait—several of whom are internationally recognized—are bidoon. Identity and belonging are recurring themes in their work. I felt that including bidoon poets and their poetry in this project could contribute a valuable and more intimate perspective on what it means to be stateless. So, during my trip, I tried to meet with as many bidoon poets as I could and asked each of them to recite a few of their poems. I made recordings and will incorporate them into the final project.

Another motivation was to highlight how in spite of all the challenges the bidoon face in Kuwait, the art created by these poets manages to transcend the community’s difficult circumstances, as the poems reach beyond the bidoon community, even beyond Kuwait. In that sense, the poems cross borders in a way the bidoon cannot, prevented from traveling because they’re denied the necessary documents.

During your last days in Kuwait you witnessed a bidoon protest for citizenship rights. This has been reported as one of the largest protests since they began in February 2011. It drew a violent response from the government. Can you talk about what you saw?

The demonstration took place in an area about 35 minutes away from Kuwait City called Taimaa. It’s a predominately bidoon area. The demonstration, which was organized by bidoon activists, was held on the International Day of Non-Violence. As described by the bidoon activists, the purpose was to peacefully protest against the exclusion of the bidoon community in Kuwait and to demand citizenship rights.

Even before the demonstration began, around 3:30pm, some 1000 Kuwaiti riot police had already positioned themselves at the site. Check posts were created at the streets leading into the areas of Taimaa, monitoring those coming in and out. It is estimated that 300 bidoon—all men—showed up for the demonstration. From what I saw, nothing in their actions showed a shred of aggression or violence. What started as a peaceful demonstration soon escalated into a violent crackdown by the Kuwait authorities. The demonstrators were beaten and arrested. Tear gas, smoke bombs, sound bombs, and rubber bullets were used over the course of the next few hours.

I saw several people injured. One man was shot in the eye with a rubber bullet—he eventually lost his sight. Two men were hit by one of the police cars. Over the next few days, some 25 bidoon, among them five minors, and other activists were arrested, including a member of the Kuwait Society for Human Rights.

Since the demonstration, many of those arrested were released on personal bonds and are now awaiting trial. Bidoon activists who have been vocal on Facebook and particularly Twitter are now wanted by the authorities. Many have gone into hiding. Little of this has received any attention from the international media.

It was the first time since starting my work documenting stateless people that I have seen a stateless community organize themselves and on a large scale, demand and demonstrate against the state for the right to citizenship. The story is far from over.

The Open Society Foundations are working to combat statelessness around the world by documenting the plight of stateless people. We also partner with local advocates to bring lawsuits challenging citizenship discrimination. We advocate for change at the international level and work to empower stateless populations to act on their own.

Sebastian Kohn is project director for sexual health and rights at the Open Society Public Health Program.

![A 30-year-old bidoon man earns a living by driving his truck around as an illegal taxi. He worked previously as a guard at a local shopping mall, for which he was paid $550 USD per month, which wasn't enough to survive. Like many bidoon, he had no choice but to start working odd jobs in the informal economy. Bidoon with the proper documents are permitted to hold drivers licenses but they cannot own or hold the title to a car. Nor can bidoon legally drive a taxi because they are not permitted to hold a taxi license. Even access to a car presents complications. “I paid 2000 KD [$7000] for this car but I don't own it. I had to have a Kuwaiti friend buy it and register it under his name.” Photo credit: © Greg Constantine for the Open Society Foundations Man driving car](https://osjicontent.imgix.net/uploads/d36b2590-2006-40c1-9831-1667ae2745c2/20121205-constantine-bidoon-statelessness-675-012.jpg?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=min&fm=jpg&h=430&q=80&rect=0%2C0%2C675%2C450)