Photos Tell Stories That War Leaves Behind

By Sara Terry

The Aftermath Project, a grantee of the Open Society Documentary Photography Project, supports photographers covering the aftermath of war. Its founder, filmmaker and photographer Sara Terry, covered Bosnia and Herzegovina from 2000 to 2005 after the Dayton Accords were signed and the war had ended. Her conviction that “war is only half of the story” compelled her to create the Aftermath Project. The deadline for their 2012 grant competition, which supports photographic projects that tell the other half of the story of conflict—what it takes for individuals to learn to live again, to rebuild destroyed lives and homes, to restore civil societies—is November 5, 2012. Sara is also bringing the work of the Aftermath grantees into classrooms. She talks here about a new partnership with Facing History and Ourselves.

In the early years of building The Aftermath Project, our primary goal was the grant competition—and the funding of an important photo story on an aftermath subject. But I always knew that it wasn’t enough to just fund good work. Without distribution for the finished project—without a way to spark conversations—it was entirely possible that important work would wind up sitting on someone’s shelf for years to come.

That’s why we’ve always done an annual book, War Is Only Half the Story, featuring the work of each year’s grant winner and finalists—and distributed it widely, sending out pro bono copies to every US senator, journalism and peacebuilding programs, museum curators, editors, industry professionals, anyone who could help forward the conversation.

This year, we’ve finally added what may be the most important component of all to our work—curriculum developed in partnership with Facing History and Ourselves, the nation’s leading developer of curriculum on genocide, post-conflict and social justice issues. Our first collaboration together has yielded six units of aftermath/visual literacy curriculum, using the work of some of the Aftermath Project’s grant winners and finalists. It’s free and can be found here (and will also be a prominent feature on our redesigned website which will launch early next year).

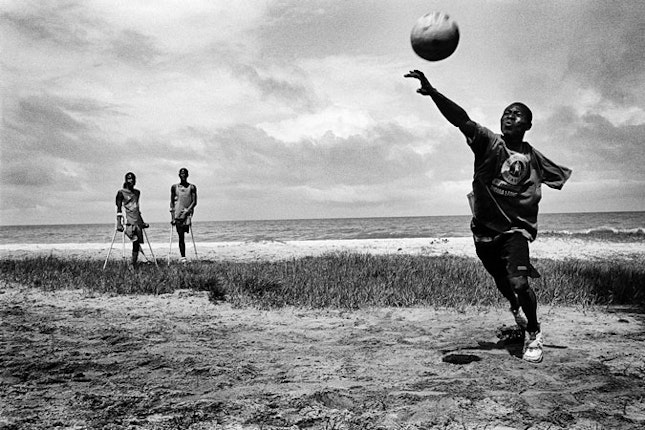

Each unit grapples with a subject like the Armenian genocide, the Wounded Knee Massacre, or the war in Bosnia. But each lesson plan also includes specific questions to help teachers and students go deeper in the photos themselves. The questions start simply enough: Where did the photographer stand to make this picture, and why did she or he stand there? What does the photographer want me to see? Why did the photographer choose to snap the shutter at that moment? And the questions build from there, engaging more deeply with subject matter in each lesson, such as the photo of two horse riders kicking up dust on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, one of the poorest places in the US: Are the riders riding to something, or away from it?

We’re not the only ones talking about visual literacy, of course. It’s becoming a hot topic among educators and a lot of other players are getting involved—see, for example, Francis Ford Coppola’s website for educators, with its emphasis on visual literacy. But there’s a long way to go to if we’re to make sure that our visual intelligence doesn’t get swept away in the ever-increasing onslaught of the media age we live in.

Sara Terry is founder and director of the Aftermath Project, a nonprofit foundation offering grants for photographers covering the aftermath of war and conflict.