Will a New Funding Strategy Leave Behind HIV’s Most Vulnerable?

By Krista Lauer

This year, World AIDS Day might be best spent reflecting on how we can make sure that socially excluded groups don’t get left behind in the global HIV response.

The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria is allocating $12 billion from donors to address the three diseases. The tricky part? How to spend it wisely. The dynamics of HIV are changing, and our approach to financing the response must change with it. It’s important that we reflect and make adjustments in real time if our funding strategies aren’t keeping up.

In March, the Global Fund did something that, on the surface, sounds logical: it approved a new funding model that prioritizes the poorest countries with the highest levels of disease. Countries with little money but lots of people living with HIV would get the biggest share of the funding, while countries with higher income and fewer people living with HIV would get less.

Makes sense, right? Actually, there are two problems here.

The first is that the best way to turn the tide of HIV may not necessarily be as simple as targeting the largest number of people. And the second is that the poorest people on the planet do not necessarily live in the world’s poorest countries.

Let’s start with the first problem. The Global Fund’s new funding model goes for sheer volume, targeting countries that have the most people living with HIV. But there are countries that have low overall HIV prevalence rates across the general population, yet suffer from devastating, highly concentrated epidemics within specific groups—for example, among people who use drugs, sex workers, transgender people, or men who have sex with men.

Targeting these smaller epidemics is crucial, especially because members of these groups often can’t easily access HIV treatment and services. People who use drugs, sex workers, and men who have sex with men may face imprisonment simply for the work they do, for who they love, or for the substances they use. They don’t necessarily think of the health system as a place of support. Simply accessing health care can risk exposing them to the criminal justice system.

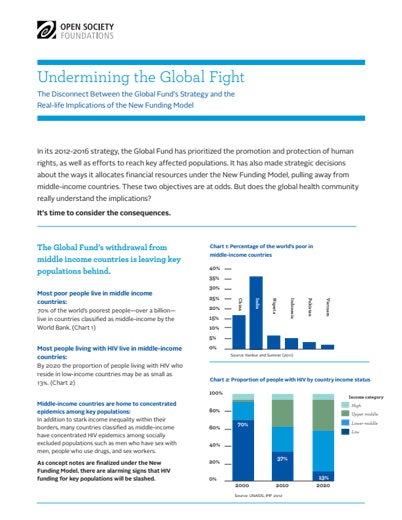

Then there’s the second issue: that the poorest people don’t always live in the poorest countries. Research shows that the “new bottom billion”—or 72 percent of the world’s poorest people—today actually live not in poor countries, but within the borders of middle-income countries—the very countries the Global Fund’s new funding model would withdraw money from.

Today, some of these middle-income countries have become epicenters of the HIV epidemic. In the year 2000, 70 percent of all HIV cases were found in poor countries. By 2020, a mere 13 percent of HIV-positive people will live in countries that are defined as “poor.”

What’s more, while the Global Fund says that middle-income countries are rich enough to pay for HIV services, the reality is that when national governments are asked to take over the responsibility of funding such services, politically unpopular measures like providing clean needles to people who use drugs—even though that’s proven to be one of the most effective ways of fighting HIV—fall by the wayside. Romania is a prime example. After it stopped receiving Global Fund support in 2010, it witnessed a stunning spike in the share of HIV cases among people who inject drugs, from three percent in 2010 to 33 percent in 2013.

The Global Fund is developing a new five-year strategy next year, and understanding the impact of the new funding model is of paramount importance. If there are elements of the model that need to be corrected, this is a prime opportunity for strategic review, and to make any necessary course corrections.

As this review takes place, the Global Fund must remember that where you spend the money, and who you spend it on, is all-important. This is exactly the thinking that guided the Global Fund’s attempt to design a better funding model. But it may have guided it in the wrong direction. As it evaluates its funding strategy going forward, the Global Fund needs to remember that the most vulnerable populations aren’t always where you’d assume they are, and that sometimes the most difficult epidemics to treat are the smallest.

Until June 2016, Krista Lauer was the director of the Global Health Financing Initiative of the Open Society Foundations.