Czech Republic

In the 1980s, the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was regarded as one of the most tightly controlled Communist regimes in the entire Eastern Bloc, even resisting the easing of controls signaled by the Soviet Union’s Mikhail Gorbachev. Only a handful of dissident intellectuals were prepared to face imprisonment and isolation by openly criticizing the one-party state.

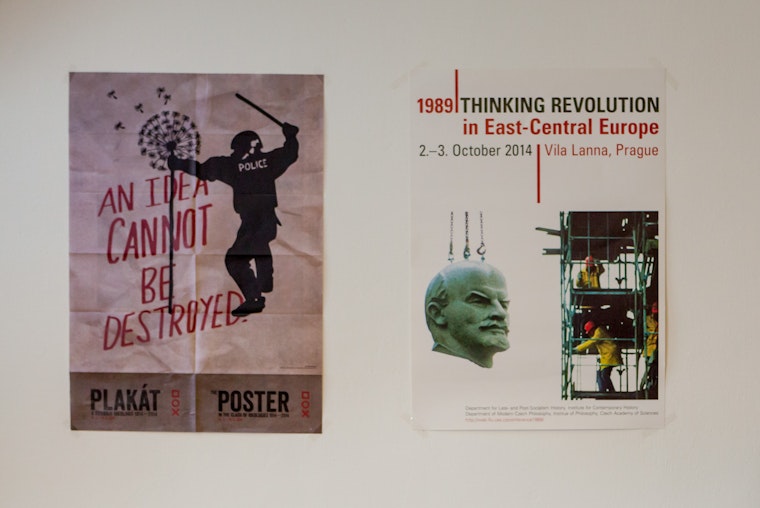

Then came the fall of the Berlin Wall on the night of November 9, 1989. Just over a week later, on November 17, riot police in Prague brutally suppressed a protest by university students, sparking further public defiance and mass demonstrations. The entire top leadership of the Communist party resigned on November 24, clearing the way for the election of the former dissident playwright, Václav Havel, as president at the end of December.

The peaceful dissolution of Czechoslovakia followed three years later, with the creation of the Czech Republic and Slovakia on January 1, 1993, led respectively by Václav Klaus and Vladimír Mečiar.

Marie Bohata

“I was one of those who really seized the opportunity—of course, it meant losing something too—to invest in the future.”

— Marie Bohata, Senior Researcher, Center for Economic Research and Graduate Education—Economics InstituteIn 1989, Marie Bohata was 40 years old.

Michal Kopecek

Sitting in a restaurant in Prague’s Pushkin Square, Michal Kopecek has much to say about 1989, as you would expect from a historian of the post-War Czech experience.

When he was 15, Kopecek was then at Prague’s elite Wilhelm Pieck school, named for a man chosen by Stalin to be East Germany’s first head of state. His school was highly politicized; many of Kopecek’s classmates came from Communist nomenklatura families, while others came from those bound up with the country’s dissident movement. This meant that the school’s students were particularly well informed. As events gathered pace, Kopecek became, he says, a runner for the revolution. Given boxes or papers, he would be told, “give it to Karel.” Karel would then give him another address with something else to carry.

It was intensely exciting, he says, but he ran so much that he ended up in a hospital with a heart murmur. Yes, it was frustrating to be there while Communism was collapsing outside, but it was not so bad; all his friends came to visit (including, he recalls, a girl he had a significant teenage crush on).

Chicken roulades arrive. Luckily, Pushkin Square is off Prague’s tourist trail. Nowadays, the town center is packed with so many visitors that you can barely hear Czech being spoken. In the late 1980s, the capital of what was then Czechoslovakia was a gloomy, grey place where wooden scaffolding propped up decaying historic houses, their crumbling masonry a potentially lethal threat to passers-by.

In 1992, Kopecek went on to Prague’s renowned Charles University, where the dramatic political changes had resulted in there being no professors of modern history. There had been no formal, official purge of the old guard academics who had prospered under the Communists. Yet, in response to intense social pressure, most had left regardless. The issue was not what you had been teaching under Communism, but whether you had used the events of 1968, and the Soviet-led invasion, to get rid of rivals. In the early 1990s, Kopecek says, anti-Communism had become a powerful tool with which to beat your enemies and advance your career. “After all,” he says, “academic politics is nothing but politics too, right?”

Kopecek says he was amazed by the speed at which former Communist societies had to adapt, and by how, 30 years later, Communism can seem as remote to young people as World War One and World War Two. Yet his colleagues who teach in high schools have found that the subject still has the power to touch raw nerves. Some have tried to use family memories to stimulate an interest in history, but this has been a recipe for poisoning the atmosphere in class. It pits those from families who cherish their anti-Communist memories against those whose families “very much dislike what they feel is an anti-Communist crusade.” Kids from the latter group then adopt “countercultural interpretations,” arguing that there were good things during that period and that “all this anti-Communist shit you hear. . . is actually propaganda, just as much as there was Communist propaganda before 1989.”

At his university, Kopecek has noticed that students are less interested in 1989 and the years that preceded it than they are in the transition period—and the question of whether people could have done things better. They see that their country today has the same problems as others in a globalized world, starting with the environment. They may acknowledge that “Communism may have been wrong,” but see it as “not our problem.”

I asked Kopecek, as an academic, about the contribution of Central European University, founded by George Soros in the early 1990s with hopes of contributing to an intellectual revival in the region. He has been closely associated with the university for some 20 years and sees it as a hugely important intellectual hub. It has brought together both Western ideas and academics and students from across the region, who get to meet their counterparts who—like Serbs and Croats, for example—might otherwise see their common history very differently.

As for civil society, Kopecek sees it maturing. In the 1990s, there was a tendency toward “NGO-ism” he says, reliant on foreign funds. Now, as at least some parts of society get richer, there is more grassroots activism than ever. He has a word of caution, though: not all of this activism is necessarily a good thing. Some of the region’s burgeoning far-right and neo-fascist movements, for example, have their roots in what he notes is sometimes referred to as “uncivil society.”

As we leave, Kopecek mentions his grandmother, a Catholic peasant from southern Moravia. She did not like the Communists, but she also resented the way that what she saw as the achievements of the local cooperative—which she and others had spent a lifetime building—were being stolen via privatization in the 1990s. “Oh Michal,” she used to say to him, “I think we lived better under Communism. . . . Nobody was stealing.” History is in the eye of the beholder.

David Tišer

“Like a majority of the LGBT community, they [made] a huge step these 30 years. Seventy or eighty percent of Czech society, they support LGBT people, so it’s different and better.”

— David Tišer, Director, Ara ArtIn 1989, David Tišer was four years old.

Tim Judah is a British reporter and political analyst for The Economist, who reported from Romania in the immediate aftermath of the fall of Nicolae Ceaușescu in December, 1989.