Closed Sea: Documentary Examines Italy’s Controversial “Pushbacks” of Migrants

By Stefano Liberti

On the May 7, 2009, then Italian minister of interior Roberto Maroni proudly announced the beginning of a new policy on the management of migration flows through the Mediterranean: “All migrant boats intercepted at sea will be brought back to Libya.”

The so-called “pushback” policy resulted in the return of nearly 1000 migrants—mostly asylum seekers from Eritrea, Somalia, Ethiopia and Sudan—to Libya, a country that has not signed the Geneva Convention and doesn’t recognize the right of asylum. Migrants forcibly returned were then put in detention centers and submitted to a variety of abuses.

The pushback operations were a direct consequence of the new alliance between Italy and Libya, under the auspices of a 2008 “Treaty of Friendship, Partnership and Cooperation.” The text, signed by the late Muammar el Gaddafi and then Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi in Benghazi, was a milestone in the relationship between the two countries. Italy committed to giving Libya $5 billion as compensation for damages inflicted during the colonial era. In exchange, Libya gave Italian companies privileged access to the oil sector and its new large-scale infrastructure program. It also assured the Italian government it would do its best to prevent migrant boats from arriving to Italy. Prime Minister Berlusconi summarized the deal as follows: “Now, we will get more oil and fewer illegal migrants.”

In May 2009, the Mediterranean became a “closed sea.” Italian military vessels stopped boats and handed migrants back to the Libyans. In fact, many of the ships were the same that previously engaged in rescue operations.

What happened on these ships? How were these operations carried out? Were the migrants identified? Were they put in a position to apply for asylum? The Italian government has never answered these questions. Migrants returned to Libya were unable to give their version of facts. They were jailed in detention camps, in a country that granted very limited access to the foreign press.

In September 2009, I was in Tripoli for the 40th anniversary of the “revolution,” the military coup that had overthrown King Idris al-Sanousi and brought to power a bunch of young military officers led by a 27-year-old colonel, Muammar el-Gaddafi. The capital city was crowded, many African dignitaries had come to join in the celebrations and cheer the aged leader.

A huge show had been staged in the Green Square, the main gathering spot on the seafront. On this occasion, journalists were allowed to come in big numbers and control was relaxed. So, I managed to sneak out of the official celebrations and meet with some Eritrean migrants in a remote suburb of the town. As we sipped tea, sitting on the floor of a small room with no electricity, they gave me their account of how a group of their fellow countrymen had been returned to Libya. “They had almost reached Lampedusa. The Italians brought them back to Tripoli and beat them up before the Libyans came and took them.”

They added that some of the migrants “pushed back” were in the Misurata detention center and that it was possible to talk to them, since they had a cell phone. I immediately dialed the number and introduced myself. A man called Yohannes agreed to tell me what had happened on the ship. “They told us we were heading to Italy. But in fact they went south. After some hours, we realized we were actually going to Libya and we started protesting. They reacted very badly. They beat us. They used sticks and tasers. We begged them. But they had no mercy. They wounded four of us. Then they handed all of us over to the Libyans.”

Yohannes added that they were in possession of a video shot with a cell phone that showed the very moment when the military ship had come across them. The video was on a flash drive, but, as they were jailed, there was no way to have it sneaked out. After this call, I called Yohannes regularly to keep contact with him and make sure that he and his fellow prisoners were not in danger of being deported to their home country.

Finally, some seven months later Yohannes was released from prison. He went back to his previous life in Tripoli, surviving on small jobs and always looking for a chance to cross the Mediterranean. One day in July 2010, he called me up and told me he had probably found a way to send the video over the internet. The file was very large and Libyan connections very poor. We had to try many times before we got it through.

The video was impressive. It showed a rubber dinghy packed with migrants. There were some women and a bunch of little kids. Suddenly, a big Italian military ship appears. The travelers are seen shouting with joy. “We are safe, we are going to Europe” they say. They all look very happy. Then another small boat approached with three guys on board. Before starting the transfer operations, they shouted: “Women and children first.” Then, the video stopped. It didn’t show the end of the story. “We hid it, protecting it from all the body searching we went through,” Yohannes told me. “When we realized things were taking a bad turn, we decided we should keep the video as evidence. Luckily they didn’t find it.”

I watched the video with my colleague Andrea Segre and we immediately thought the story deserved to be told to a broader audience. We had worked together on previous documentaries about the impact of migration cooperation between Libya and Italy. The first, “South of Lampedusa” (2006), was shot in the Sahara right after the first migration agreement between Rome and Tripoli, which resulted in thousands of migrants being deported from Libya to Niger and dumped into the desert, even though they had been living in the country for decades. The second film, “Like a man on Earth” (2008), was shot among the Ethiopian refugees in Rome by Andrea and the Ethiopian filmmaker Dagmawi Yimer. It described the conditions in Libyan detention centers, where all of them ,including Dagmawi, had spent months or even years. It was a story of abuse and despair that concerned us directly—some of these centers had been financed and built by the Italian government.

This next step, we felt, was to explore direct effect of the friendship treaty. And Yohannes’ video gave us a way into the story. We thought the people in the footage could become our protagonists—they would tell the rest of the story. But challenges remained. Journalists’ access to Libya was strictly controlled and we would never get a visa for the kind of project we had in mind.

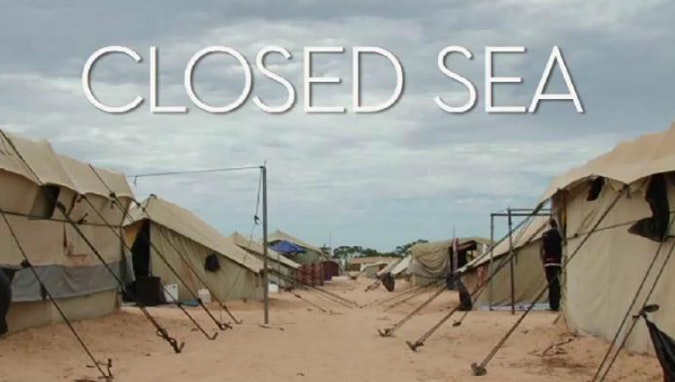

Then, in February 2011, the Libyan war had opened a window of opportunity. Rebel groups took control of the eastern part of Libya. There was chaos on the ground and the great majority of migrants fled to Tunisia for shelter. Many of them ended up in the UN-refugee camp of Shousha, near the Libyan border. They were given tents and were enrolled in a UN-resettlement program. They stayed in the camp, where they would spend some time waiting to be sent to third countries willing to accept them. For the first time, migrants previously pushed back by Italy were accessible.

We immediately left for Shousha to learn what had actually happened on the Italian vessels. When we got to the camp, we realized that our goal was a common one, shared by the men and women who had been deported. When we explained our idea, they enthusiastically rallied to the project. They wanted to tell their story not only to get some kind of justice, but also to “avoid a repetition of the same mistakes”—as nearly all of them told us during our interviews. Together, we wanted to create something that could become an advocacy tool for the future—we wanted to influence future policy.

Mogos Berhane, one of our protagonists, recently wrote to us after watching the film. “Deep inside, I am convinced that this documentary film will make a shift in the attitude of people towards refugees on the northern part of the Mediterranean Sea,” he said. “And the world will not repeat the same mistake against refugees. Our moral values to provide human beings with decent living should never be washed by our greedy drive for political and economic interests.”

His words reflect our hope.

The pushback policy is currently suspended. And Italy has been condemned by the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg for the operations conducted in May 2009. But Italy’s new government has already started negotiations with Libyan transitional authorities to find a common way to tackle immigration by sea. The policy seems to revisit the old scheme: migrants should not be allowed to come, even though they are asylum seekers fleeing from wars and political persecution.

Stefano Liberti is an award-winning journalist and author.