Is Diversity a Threat to Freedom?

By Edward Mortimer

Diversity is both a condition and a result of freedom. Without it, there would be no alternatives for people to choose freely between; and since in practice people make different choices, their freedom produces a diversity of outcomes.

Yet in the last few decades many people living in liberal democracies have come to see certain kinds of diversity as a threat to freedom. They see some other groups within their societies as placing a lower value on freedom than they themselves do (or think they do), or even as being actively hostile to it. Or they may feel that, in the name of “respect” for other people’s beliefs and customs, they are being prevented from exercising their own freedom to live as they choose and say what they think.

With support from the Open Society Foundations and other funders, the Dahrendorf Programme for the Study of Freedom at Oxford University undertook a research project to see how such tensions had been handled in five major Western countries, and whether specific policies or approaches had worked better than others. This culminated in a major conference of experts—academics, policymakers and journalists—held in Oxford in May 2013. Three of the participants—Timothy Garton Ash, Kerem Öktem, and myself—then undertook to distill some general lessons for future policymakers, while recognizing that circumstances differ from country to country, so that there can be no “one size fits all” solutions.

We deliberately avoided taking a position for or against “multiculturalism,” since we found that meanings assigned to this term vary with the speaker and the context. Nor have we taken a view on immigration policy as such. Our concern is with the policies required to make a success of societies which are, as a matter of fact, multicultural, as a result of migrations that have already happened and could not be reversed even if that were considered desirable. (In fact, for a range of economic and political reasons, there is every reason to believe that they will continue.)

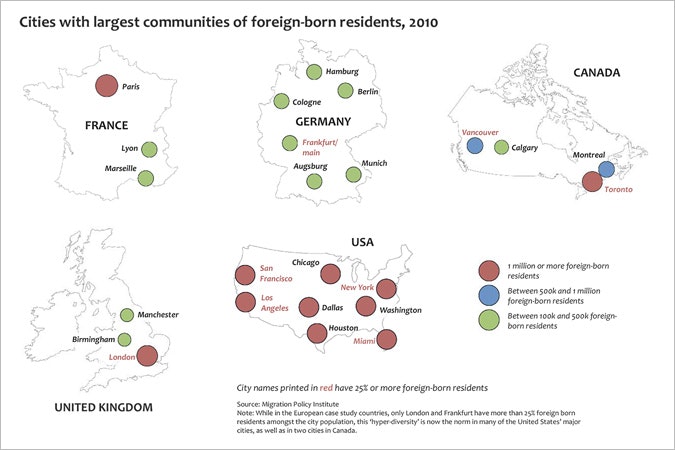

The extent of this diversity is well conveyed by the graphic above, which shows that 24 cities in the five countries we studied now have more than 100,000 foreign-born residents, 14 of them more than 500,000, and 11 more than one million, while in eight of them these residents form a quarter of the population or more.

We believe that diversity of this type can indeed coexist with freedom, both benefiting from it and contributing to it, but only if certain principles are respected. These principles are set out in our report, Freedom in Diversity [pdf], in the form of ten lessons. Rather than attempt to summarize them all here, I will focus on two, the seventh and eighth, titled respectively “Representation in the media” and “The duty to speak out.”

Treatment of minorities in the media is harder to quantify than some other aspects of integration, and there is a lack of comparative or easily comparable data. It is therefore not always easy to make objective judgements. In many contexts good news is no news, and the media see their main task as being to report what is wrong. Consequently almost every group that attracts media attention feels that it is misrepresented, with undue emphasis on the negative.

Yet even after allowing for that, some media do seem to go out of their way to highlight stories in which “immigrants” (usually including people who are not strictly immigrants but the children or grandchildren of same) figure as criminals, welfare scroungers, or terrorists. Other media may not seek to reinforce these stereotypes deliberately but are influenced by them and therefore do so in practice. Certainly they have a responsibility to report on minorities—as on any other topic—fairly and objectively, but the line between responsibility and political correctness, or even self-censorship, is not always easy to draw.

Partly for this reason, our report focuses on representation not only by the media but in the media. It is important that minority faces and voices should be well represented among media professionals—those who can be seen and heard on TV and radio, those who report and comment in print or online, and also those with editorial or gatekeeper functions who decide what the public should or should not see and hear.

But it is also important that the public in general, and especially those whose celebrity or profession gives them privileged access to the public eye or ear, do not leave it to media professionals or to the law courts to “set the record straight.” Our report seeks to make a clear distinction between what must be required by law in a free country and what is merely desirable for living together in a free country in mutual enrichment.

This latter category of obligations cannot be compelled: it needs to exist in people’s hearts and minds. Thus a better common life in today’s diverse societies ultimately depends less on legal compulsion, and more on enabling people of different cultures and persuasions to feel that they actually need to live together, and can do so without feeling threatened, because they are all members of the same society and nation.

The battle for public opinion does not belong mainly in the law courts. But that only makes it more important to fight it where it does belong, namely in the media and public debate. Slanders and stereotypes should not be left unanswered, as they may have a corrosive influence on social cohesion and our chances of living together in freedom and diversity.

This may be particularly true in social media, where there is currently a tendency to compensate for perceived or real constraints on what may be said in the mainstream media by indulging in hurtful and inexcusable forms of racist and sexist abuse. That is why we strongly recommend that “public figures, and people with a significant presence online, should challenge stereotypes and misleading generalizations about any group.”

Edward Mortimer is a Fellow of All Souls College, Oxford, and senior program adviser to the Salzburg Global Seminar.