How New Technologies Can Help—and Hurt—Migrant Workers

By Elizabeth Frantz

In 2017, a recruiter arrived in Ojo de Agua, Mexico, with an enticing pitch. For a few thousand pesos, he said, he could arrange for documented employment in the United States. The jobs were waiting with H-2 visas attached. The claims caused a stir in the small community in Mexico’s Hidalgo state. Offers like this didn’t come along every day.

Three residents paid the recruiter, unaware that the jobs he spoke of didn’t exist. Since he was from out of town, no one in Ojo de Agua knew of his reputation as a scam artist. And because migrant workers operate within a sprawling global supply chain that isolates individual laborers, they felt there was no way to verify the promises he had made.

Such scams may become rarer in the future. An increasing number of digital platforms are being created to connect and organize workers, and to enable them to share their experiences and advocate for better conditions. The potential for such technology to improve the lives of low-wage migrants is huge. Utilized responsibly, it could level out many of the power imbalances that enable exploitation. But it also holds risks. Without proper buy-in, worker-oriented design, and safeguards to keep it from being used exploitatively, digital tech could disempower workers even more.

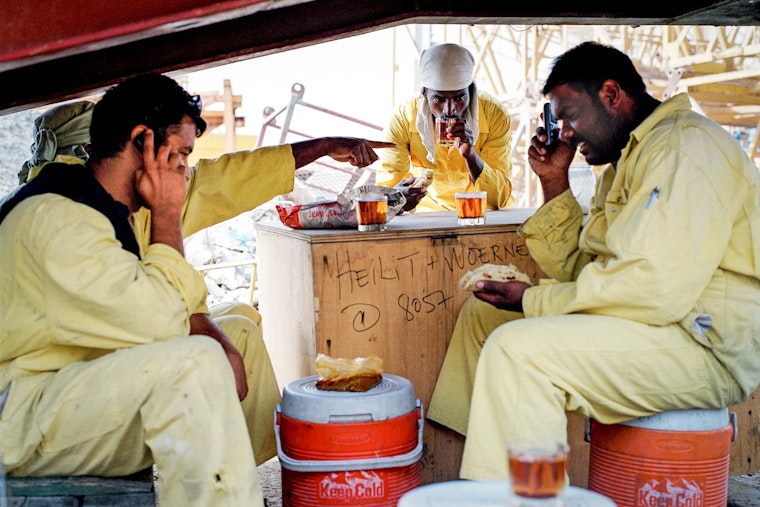

Though it’s unclear how many of the world’s 150 million migrant workers [PDF] rely on digital technology, a 2009 study [PDF] found that “mobile phones are ubiquitous among most groups of foreign workers.” It’s safe to assume that, since then, they’ve become even more pervasive. A new report funded by the Open Society Foundations’ International Migration Initiative, Transformative Technology for Migrant Workers, shows how mobile tech is a critical tool for a uniquely mobile population.

The report details the promise and the perils of digital connectivity for this group. Recent innovations to create reporting platforms, for instance, collect information from migrant workers on the ground. This information can help streamline grievance processes, identify safety concerns, narrow the gap between manager and employee, and generally act as a barometer of workplace well-being.

In this way, reporting platforms have the potential to give workers a voice. At the same time, however, they amass data about those workers, and how that data is used—to benefit or to exploit them—is a clear concern.

Data aggregation can help companies respond to workers’ needs, but it can also drown out individual complaints, creating an overly positive view of a working environment. Companies could point to these broad swaths of data to “prove” that their workers are happy, and by extension, use the tools as a way to avoid engaging in collective bargaining. Ultimately, the power of tech-enabled tools to reduce labor exploitation in supply chains hinges on whether there is the political will to act on reports of abuse when workers make them.

In the hands of the workers themselves, data can be invaluable. Things like digitized contracts and tracked wages help workers make sure they get what they’re owed. In some cases, these evidentiary materials can be turned into legal claims using platforms like Impowerus, which connects community organizations with local legal aid clinics.

Other platforms are designed to connect workers with each other directly—an important resource for a population whose disconnectedness is often used against them. For instance, on Yelp-style platforms like Contratados, workers can rate and review their recruiters. Other tools allow users to evaluate their employers on metrics like “correct pay” and “respect for staff.”

These sites can foster a sense of worker community and empowerment that may be particularly vital for workers who are otherwise physically isolated, such as domestic workers. But just like reporting platforms, worker-to-worker platforms have their drawbacks. They’re susceptible to fraudulent self-reviews by employers, who might also use them to monitor their own employees. Large numbers of positive reviews can overwhelm smaller—but just as important—negative ones. And convincing a critical mass of workers to use these sites is both difficult and key to their success.

Among digital technology’s most basic functions is facilitating the flow of information, and the best of these provide this information in ways specifically geared toward their users. For migrant workers, this means packaging information in low-bandwidth formats that don’t eat up phone data and using visual mediums like comics that cut across language barriers. One platform called Shuvayatra, allows users to submit questions to organizations that support safe migration. Another, called WorkIt, keeps hourly employees informed about their company’s workplace policies.

As Ojo de Agua’s example shows, this connectivity, when oriented toward empowering workers, can impact real lives in significant ways. After the three residents there gave the fraudulent recruiter their money, one of their sisters attended a workshop at which a member of Centro de los Derechos del Migrante taught her to use Contratados. She showed her brother the platform, who used it to identify his fraudulent recruiter. Within 24 hours, authorities had caught the man and made him return the money. It shows that the right tool in the proper hands carries enormous potential to level the playing field and open the door to an honest day’s work.

Elizabeth Frantz is acting co-director of Equity at the Open Society Foundations.