A quarter century before his own death, Bill Moyers, one of the most celebrated journalists and true public servants, began to think about what few Americans wanted to think about—the end of life. How could it be that while it’s the one certainty connecting us all, we often avoid the subject, deny its inevitability, and thus lose the opportunity to prepare. Moyers, who passed away this week, decided to dedicate a series to answering that question and show Americans that death and dying does not have to happen in the shadows.

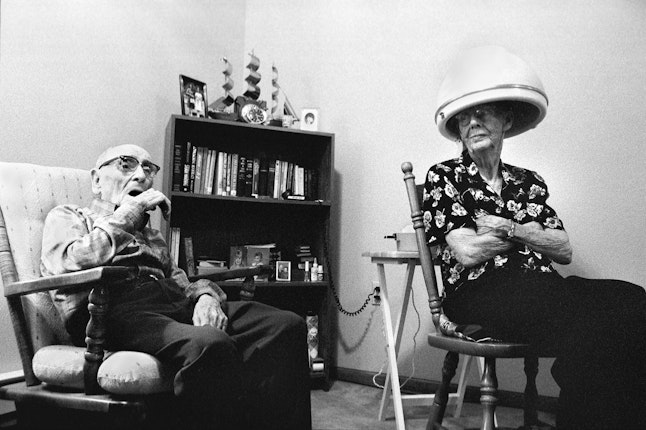

In 2000, Moyers hosted and produced On Our Own Terms: Moyers on Dying. Over four episodes, he took viewers from the bedsides of people in their final moments to the frontlines of a movement to improve end-of-life care led by the Project on Death in America (PDIA)—an idea inspired by George Soros.

George understood how the country was programmed to think of death as a failure, and thus conversations around death as taboo. “I didn’t talk about my father’s death,” he has written, recalling how Tivdar Soros ended up dying alone and suffering. “I kind of denied his dying.” Contrast that with the experience he had when his mother was dying. She’d joined the Hemlock Society and even asked George if he’d help her when the time came. He had no desire to do that and fortunately didn’t have to, but at least they had the chance to reconnect, talk about the trajectory of her life, and how she wanted to die. As she lay dying, the family, including George’s children, were able to participate in her end. “Her dying was a really positive experience for all of us,” he wrote.

If only we could all be so prepared for our own and our family members’ deaths. My mother, who suffered through stage four lung cancer, kept trying to have conversations with me about her death, and every time, I deflected her attempts as morbid. She never got to have that conversation with me, and I never got to share her experience of dying. I’m sure thousands in America have experienced that regret, and for many that means experiencing unnecessary physical, spiritual, and psychological suffering.

George wanted to change both the culture and policies around death and so, as he always does when he has an idea, he asked his people to assemble a group of experts in medicine, law, ethics, and gerontology to brainstorm a strategy. Over a weekend at his home, representatives from AARP and the American Board of Anesthesiology, and leaders in the field began dismantling the institutional barriers surrounding end-of-life care. And so, by 1994 PDIA was born.

Kathy Foley, chief of palliative and pain care at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, was asked to run the project, together with a remarkable board of directors including—Susan D. Block, a psychiatrist involved in hospice and started palliative care education at Harvard, Robert (“Bo”) A. Burt, Yale University constitutional lawyer, ethicist, and author of Taking Care of Strangers, Andy Billings, who would found the palliative care center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Robert N. Butler, founding director of the National Institute of Aging, David J. Rothman, a social historian at Columbia University and author of Strangers at the Bedside, Joanne Lynn, medical ethicist and lead author of the SUPPORT study evaluating illness and treatment of 10,000 seriously ill hospitalized patients, Patricia Prem, a social worker and friend of George who organized the initial meeting, Ana Dumois, a social worker and community health expert and advocate, and William Zabel, an expert on ethical wills.

“In America, the land of the perpetually young, growing older is an embarrassment, and dying is a failure. Death has replaced sex as the taboo subject of our times. Only our preoccupation with violence breaks through this shroud of silence.”

— George Soros, Reflections on Death in America, 1994

The group decided to focus on transforming medical practice itself, creating a prestigious faculty scholars program, using professional recognition and financial incentives to encourage medical professionals to view end-of-life care as a fundamental medical responsibility. By targeting teaching hospitals and offering professional development, PDIA began shifting the cultural conversation. They supported research, provided grants, and created platforms for medical professionals to explore more humane approaches to dying.

Soros’s fundamental belief was simple: Death deserves the same careful attention we give to life.

I recently had the chance to talk to Kathy Foley about the lasting achievements of the Project on Death in America and how it’s changed the culture, and where we are today. One statistic she told me really stood out: In 1993, there were no hospitals with palliative care centers. Today, over 75 percent of hospitals with more than 50 beds have palliative care centers.

Starting Conversations and Breaking Taboos

Kathy, thank you for taking the time to talk to us. I wonder if you can start by telling me about those early brainstorming sessions with that incredible group of experts?

When we first came together, we were struck by some alarming statistics—60 percent of Medicare’s budget was being spent in the last six months of life. ICU units were being opened, and no one was asking patients about their wishes or how they’d like to receive care. In a major study, Joanne Lynn found that 50 percent or more of dying patients were reporting uncontrolled pain, their wishes about end-of-life care were unknown or not honored, and half of the family members were made bankrupt by their family member’s hospitalization. We realized something fundamental needed to change in how we approach death and serious illness.

So how did you approach transforming end-of-life care at a time in this country when such conversations were so taboo?

Well, we developed a multi-layered strategy that was quite innovative for its time. Our major approach was to create a network of 87 faculty scholars— predominantly physicians, nurses, and social workers who would become palliative care experts, leaders, educators, and role models. We weren’t just funding research; we were deliberately building a field of expertise. Our goal was to create systemic change by developing academic leaders who could influence institutional practices and challenge existing cultural attitudes about dying.

What challenges did you encounter?

The challenges were profound and deeply cultural. Americans historically viewed death as something to fight against at all costs. We had to overcome massive resistance to even discussing dying. Health care institutions were focused almost exclusively on cures. Many medical professionals didn’t know how to communicate effectively about end-of-life wishes. There was also significant confusion between palliative care and hospice care. We had to educate people that palliative care isn’t just about dying, but about supporting patients with serious illnesses and improving their quality of life.

Palliative Care at the Forefront

What has become of the 87 faculty leaders you identified at the time?

Actually, what is extraordinary is that they are the current leaders in palliative care and have been for the last decade. James Tulsky, Tony Back, and Bob Arnold created VitalTalk, an extraordinary educational communications program available nationally that grew out of their realization that doctors didn’t know how to talk to patients about end-of-life care. Tulsky is now at Harvard. Back is at the University of Washington and Arnold led the University of Pittsburgh Institute for Doctor-Patient Communication.

“We had to educate people that palliative care isn’t just about dying, but about supporting patients with serious illnesses and improving their quality of life.”

— Dr. Kathy Foley

Diane E. Meyer a geriatrician and ethicist at Mount Sinai along with her PDIA team went on to lead the Center to Advance Palliative Care, which produces a report card rating each state’s palliative care. The center also provides resources and toolkits to support hospitals and health care providers to develop and maintain palliative care initiatives. R. Sean Morrison, now chair of Geriatrics at Mount Sinai, went on to create the National Palliative Care Research Center, which has provided 15 years of philanthropic support to new and mid-career researchers in palliative care. Unbelievably, less than one percent of the National Institutes of Health budget went into palliative care when they started this effort.

At that time, it seems cancer patients really had only two options. Treatment or hospice. Cure or death. Is that right and how did you address this?

I’ll tell you a side story. In 2001, we published a report called Improving Palliative Care for Cancer, which pointed out that in the attempt to cure we had forgotten to care. In fact, the only program in the government that talked about people who died of cancer was not the National Cancer Institute but rather the Department of Defense. In memorializing their dead, they included women in the military who died of breast cancer. The National Cancer Institute was afraid to talk to the public about dying. In one study, Zeke Emanuel, a medical oncologist and ethicist, found that in the last six months of life cancer patients were receiving two and three different chemotherapy regimens and there was no conversation about alternatives. The only alternative was hospice which meant you’d die in six months. For Americans it’s “give me liberty or give me death.” Death is always second choice.

Educating and Empowering Communities

Can you tell me about some of the specific communities in this country and how the project focused on or supported them?

Absolutely. Richard Payne, an African American leader in pain management, led a project exploring why African American patients often chose aggressive intensive care unit care. He found that many felt palliative care was “second-class care,” a legacy of systemic health care inequities. For example, an African American prostate cancer patient of his resisted palliative care, saying, “how long it took me to get here, and now you’re going to give me second-class care?” Rich developed a curriculum called APPEAL to educate both health care professionals and the African American community about end-of-life care, recognizing the importance of faith, community, and spiritual considerations. PDIA started that effort, and then the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation supported it as a national program. What was wonderful about George is that PDIA didn’t need to take any credit, so we could collaborate and co-fund without concern for attribution.

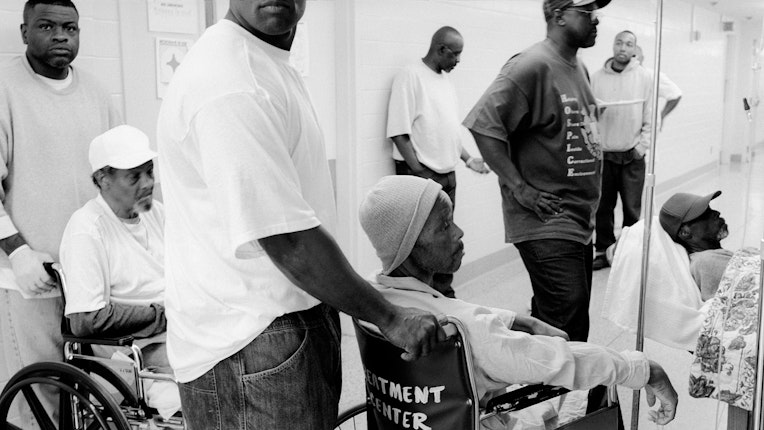

You also did a project that resulted in a documentary in Angola Prison. How did that come about?

PDIA collaborated with another U.S. program called Crime, Community, and Culture. We discovered that up to 2,500 people were dying in prisons with virtually no compassionate care. At Angola Prison in Louisiana, where the majority of inmates were there for life, the family members not only didn’t get a chance to visit their dying relative, but often didn’t even know they were dying. Funeral services were held and prisoners made coffins for the dying, and the dead were buried in unmarked graves. We supported a documentary project on the creation of the first prison hospice program called the Angola Prison Project. It was extraordinary to see inmates becoming hospice volunteers, often passing pain medication to dying inmates through locked doors. In one powerful moment you hear a volunteer saying, “the last person I saw dying was the person I killed,” and now he was a hospice volunteer, caring for a dying fellow prisoner. The project led to significant policy changes, including improved compassionate release policies.

What other specialized projects did you support?

We had fascinating projects across multiple medical specialties. Dr. Lewis Cohen studied end-of-life care for patients with chronic kidney disease. Judy Nelson worked on ICU care, while Steve Pantalat created the field of palliative care for hospitals. Tammy Quest did amazing work introducing palliative care to emergency care. We deliberately expanded beyond cancer to create specialized palliative care approaches for different patient populations—from AIDS to pediatrics, from neurological diseases to heart conditions. The hope was that each disease would have a palliative care expert driving the research and clinical practice.

Shifting the Discourse on End-of-Life Care

What were some of the project’s most significant achievements?

In 2006, a new medical specialty in hospice and palliative care medicine was approved in the United States. CAPC, the Center to Advance Palliative Care, dramatically increased palliative care programs in hospitals with more than 50 beds from zero to over seventy five percent. The National Palliative Care Research Center supported research training and support to new investigators.

“The project fundamentally transformed how Americans understand and approach end-of-life care, and created a network of leaders in palliative care, who changed institutional and cultural attitudes, and developed more comprehensive approaches to serious illness.”

— Dr. Kathy Foley

When the National Academy of Medicine releases reports, they are profoundly influential in how academic medicine approaches care because they are always evidence based. We funded two such reports: Approaching Death, in 1997, and When Children Die, in 2003. These were very influential in changing research priorities and clinical practice for the care of seriously ill adults and children. They served as calls to action to health care providers. Our project ended in 2003, but the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) issued a report in 2014 called Dying in America, and more recently has supported a series of roundtable meetings and publications on people with serious illness helping to expand palliative care beyond just cancer. Perhaps most importantly, we started changing how people think about end-of-life care from seeing it as simply about dying to understanding it as a holistic approach to supporting quality of life.

So many of Soros’s projects are international, did you want to expand?

Yes. In 1998, we began an international initiative that was truly exciting, working with Open Society’s national foundations to develop palliative care initiatives, create national policies, improve drug availability, and develop educational programs. One of our proudest moments was securing a World Health Organization resolution requiring palliative care services in each country. Countries like Hungary and Romania became star examples, creating national policies, making pain medications more accessible, and developing comprehensive support systems.

Taking End-of-Life Care Conversations into the Mainstream

What made your approach to funding unique?

We were intentionally collaborative and humble. George Soros always said to me that if I didn’t have grants that failed, I wasn’t funding the right people. We weren’t interested in taking credit; we wanted to make meaningful change. We supported innovative projects across different medical specialties and were always willing to let other organizations take the leadership and receive the credit. We were fortunate to work with other funders like the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Kornfeld Foundation, and so many others who have carried on the work to develop palliative care. We carefully avoided controversial debates like physician-assisted suicide, focusing instead on improving care and communication.

How did you raise public awareness about these issues?

We collaborated with Bill Moyers, who was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, in creating a television series to bring these conversations to the public called, On Our Own Terms: Moyers on Dying. We helped Moyers identify the programs and clinicians included in the series, and almost all of them were PDIA grantees.

And the project must have had an enormous influence because the film describes Moyers as going from the bedsides of the dying to the front lines of a movement to improve end-of-life care. That’s very compelling evidence of the project’s long legs. What do you see as the project’s lasting legacy?

The project fundamentally transformed how Americans understand and approach end-of-life care, and created a network of leaders in palliative care, who changed institutional and cultural attitudes, and developed more comprehensive approaches to serious illness. Perhaps most importantly, it shifted the conversation from simply extending life to emphasizing quality of life, proving that palliative care isn’t about giving up, but about providing the most compassionate, patient-centered care possible. We help support the clinical researchers who developed the evidence base for palliative care and the educators who helped develop the clinical training programs.

What challenges remain in end-of-life care?

We’ve made tremendous progress, but significant challenges persist. We still need more trained professionals, sustainable funding, and continued policy advocacy. The rise of for-profit hospice care is concerning, and the opioid epidemic has complicated access to pain management. Our work continues through many organizations like the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, the Hospice and Palliative Care Nurses Association, the Social Work Leadership Group, the Center to Advance Palliative Care, and the National Palliative Care Research Center. But we must keep pushing to balance cure-focused and care-focused approaches in healthcare.

Elizabeth Rubin is an award-winning journalist who has spent over two decades reporting from conflict zones across the globe, from Afghanistan and Chechnya to the Balkans and the Middle East. Her work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and other leading publications.