Murder in the Name of Honor: An Interview with Rana Husseini

By Marla Swanson

Journalist, feminist, and human rights defender Rana Husseini is one of the world’s most influential investigative journalists, whose reporting has put violence against women on the public agenda around the world.

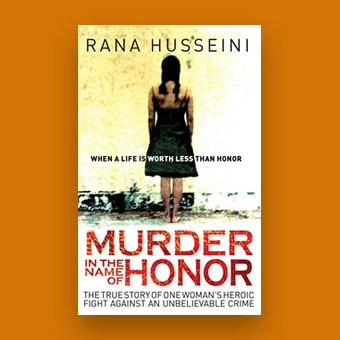

The Open Society Institute held a launch for Husseini’s new book, Murder in the Name of Honor. She recently spoke with Marla Swanson of the International Women's Program about the issue of "honor" crimes.

How did you get involved in working on the issue of so-called honor crimes?

It was a story that I came across early in my career. I was appointed as the crime reporter for The Jordan Times in September 1993 and on June 1, 1994, I read a small story of a girl who was killed by her brother in a poor neighborhood. When I went to investigate I was shocked to learn more of her story. She was raped by one of her brothers and he attempted to kill her because she told her family. She became pregnant, underwent a secret abortion and was married off to a man 34 years her senior. Six months later, this man divorced her and the day he divorced her, the second brother killed her blaming her for the rape. When I spoke to the uncles who were part of the plot, they blamed her for the rape and accused her of seducing her brother.

I reported the story and the following day, an influential woman called that newspaper screaming and yelling at my editors that they should stop me from reporting these crimes because this is not us or our society. So I became even more enraged about it and decided to show her and everyone else that this is our society and we need to work on changing such issues. Later, I went to the courts and discovered that the killers were getting away with lenient sentences of six months, one year maximum. So I decided to document this as well since no one was really talking about it during that time.

Can you tell us a bit about the book, Murder in the Name of Honor, and what motivated you to write it?

What motivated me was that I needed to tell the stories of these women who were killed. I had accumulated a lot of experiences and traveled to different places to talk and hear other countries’ and individuals' experience. So I decided to write a book back in 2000 to be a reference and documentation of these problems. At that time, there were hardly any books about this issue. I started writing the book in 2002. I had prepared an outline in 2000 and started looking for publishers after that.

I also wanted the book to be an advocacy tool for activists in other countries, and at the same time I wanted to document the work that was done in several countries, including Jordan. I include activism work being done in several countries around the world, including the UK, the US, Europe, Pakistan, Turkey, Palestine and Jordan. I end with a chapter of recommendations of what needs to be done and also to give hope for abused women who think they are alone or cannot seek help. Finally, by documenting so many stories, I wanted it to be an eye-opener for any women who are living under dangerous circumstances and they do not realize it. I want it to be a sort of warning for women. At the end of the day, I want to be able to save women’s lives, and that is the most rewarding thing one can achieve in this life.

What are some of the goals for the book and how do you hope it will be used?

In addition to what I said above, I want to be a credible source, raise awareness, give hope to women, give solutions, and document cases and efforts around the world.

What has the response to the book been so far?

I have been receiving positive feedback from people inside and outside Jordan. People I know and others whom I do not know. I have been invited to speak at some events and during my UK and US book tour I have been hearing positive feedback from people who are interviewing me or others who come to the event and have already read the book. So things look good so far. We will see more reactions when the Arabic edition comes out in a month’s time.

How widespread is the phenomenon of so called honor crimes/killings worldwide?

I believe so-called honor killings happen all over the world and are reported in countries such as Brazil, Greece, Italy and countries such as Turkey and Pakistan to name a few. So I would say that these crimes are not restricted to any society, religion or nation. The estimates based on UN figures in 2000 are 5,000 killed every year in the world, but unfortunately I think the number is much higher.

What positive changes have you seen over the years as a result of your and others’ push to uncover honor crimes (in Jordan and elsewhere)?

We have witnessed lots of positive changes in Jordan. The issue is no longer taboo and is heavily discussed in the press and among citizens, government officials NGOs and other figures in society. I can tell you that there has been a major change in the mentality of people in Jordan. People are now more open to and aware of this issue. Voices that are against these crimes and lenient laws are growing and there is more acceptance towards the work that is done by the government and civil society to end these crimes. So things are moving in the right direction, but it will take time and it is our duty as good people in society to make change happen. I am a very optimistic person and I believe that we have to always be optimistic to make change happen.

On the legal part, the government now acknowledges the problem and talks about figures and measures that it will adopt to help curb these crimes. A few years back, the Jordanian government opened the first family reconciliation house that basically aims at helping abused women, their children. There is a major change in the way the judiciary is handling these cases. We see harsher penalties than in the past. Judges have become more aware that they need to hand out stricter punishments against perpetrators of such crimes. More recently, the Criminal Court announced it was designating a special tribunal to try so-called honor crimes cases and it is expected that they will be applying the law and passing harsher punishments for such murderers.

There are constant political and social activities and awareness campaigns to address this issue, while at the same time bearing in mind that the judiciary is the highest authority in Jordan that should be respected. There is work on some of the laws that offers leniency to killers but no concrete changes were made yet. Internationally, many countries are starting to realize the gravity of so-called honor killings and many have initiated their own campaigns and activities such as Pakistan, Syria, Turkey, Lebanon and Palestine.

Do you think the general public in Jordan and elsewhere has been made more aware of the seriousness of the problem?

Yes. I can feel that the voices rejecting these crimes are much more than before and especially among men. Now when I go and lecture I have men who back me up and want to see change. In the past, they would declare openly that they would kill their sisters if they had to. Things have changed but not 100 percent.

Can you give some examples of any kind of interventions – for example, prevention or response services, policy initiatives, advocacy campaigns, etc. by various actors, you have seen that have been successful in helping to decrease or end the practice?

I think that Jordan's civil society activity in the late 1990s is a good example on how it helped raise awareness and change people's attitudes. The issue is no longer taboo and people discuss it regularly among themselves, as well as government officials, the leadership and the media. Even universities are initiating dialogue and drama is being used to tackle this matter.

Do you and other women’s human rights activists working around the issue receive threats intending to stop you from reporting on honor crimes and continuing your activism on the issue? How do you deal with this?

I have received a few emails that asked me to stop reporting about these crimes. Some women’s NGOs have had some threats as well but no incidents were reported and we hope it remains this way.

What is the long-term impact on the families of the victims after the crime? Have you come across perpetrators who have regretted their crimes against their female relatives?

Of course these crimes do not help or solve the problem as families think. They actually start new problems and especially for the person who was chosen to kill. I have met some who regretted killing the female relative they lived with and loved all their lives. Others were too depressed to talk about it. I think that some of the killers are also victims because they do not want to kill, but societal and family pressure turns them from normal human beings into killers.

Are there any recommendations you have as a result of your research on this subject?

Yes. My book ends with a lot of recommendations. We have to continue to raise awareness, encourage religious and community leaders to speak up against these crimes, encourage women and let them know they are not alone and that they can seek help. We should work on humanizing the victims and telling their stories to the world. We should work on improving the education system. Governments should improve their services to victims and more NGOs should be encouraged to do work targeting laws that discriminate against women.

What can an organization like the Open Society Institute do to help end these kinds of women’s human rights violations?

I believe all human rights organizations should constantly address the issue of violence against women in a global manner. These organizations should not point a finger at a certain country, religion or class and should instead tackle it in a broad manner since violence against women is an international phenomenon and not restricted to a society or religion or class. The Open Society Institute could also work to support women’s NGOs that are helping women who are victims of abuse or in need of assistance.

Until April 2012, Marla Swanson was senior program officer with the Open Society International Women's Program.