Nigerian Democracy’s Uncertain Future

By Udo Jude Ilo

Last month, Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari, a 76-year-old former military general, won his second term in an election marred by low voter turnout, legal controversy, and violence—which left at least 50 people dead. The outcome of the process was not merely a travesty for Nigeria; it was a warning sign to advocates of democracy and open society everywhere.

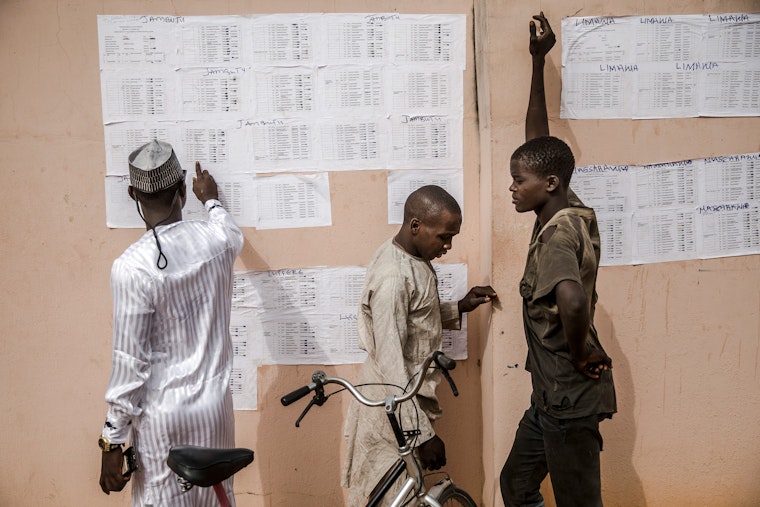

Just hours before polls were scheduled to open, the country’s Independent National Electoral Commission postponed the vote by a week. By then, thousands of registered voters had made long journeys to their home districts to cast their ballots and literally could not afford to wait idle for another week. Threats of violence by Islamist extremists, logistical breakdowns, and deliberate intimidation of voters played a role in the low turnout of voters across the country. Worrying cases of intimidation of officials of the election management body added to a pattern of orchestrated attempts at undermining key democracy institutions.

When Muhammadu Buhari won his first election in 2015, he became Nigeria’s first political leader to succeed an incumbent via the ballot box. This was a milestone for multiparty democracy in Africa. The recent election, on the other hand, represents a setback for Nigeria—and for Africa as a whole. Indeed, there is reason to fear that if the decline in standards is not urgently addressed, it could be the beginning of a progressive decline in the quality of elections throughout the region.

In the face of these challenges, civil society groups throughout the country still worked diligently on behalf of Nigerian democracy, partnering with institutions focused on the nuts and bolts of the electoral process. They also developed a so-called threshold document to outline a set of conditions that electoral institutions, political parties, and security agencies must fulfill to give credibility to the electoral process. Despite these laudable efforts, however, there is no denying that, by the standards of an open society, the election was a failure.

What lessons can civil society groups, in Nigeria and beyond, draw from this experience? How can civil society organizations broaden their constituencies and bring leaders from business, labor, and organized religion into campaigns for credible elections? With more than one-third of the world’s population set to vote in elections this year, these are not abstract questions.

First, there must be a comprehensive audit and review of what happened in the 2019 elections. This process must be independent and driven by the Nigerian people (in close collaboration with international experts). It is imperative to identify what went wrong with the electoral process and to examine the influences in Nigerian political society that makes electoral malpractices acceptable.

Second, Nigeria’s government should establish an electoral offenses commission which is empowered to hold accountable those that committed offences during the election process. To be sure, given the government’s obvious interest in avoiding scrutiny, the international community should join with those in Nigeria who are calling for such a commission. The international community should consider sanctioning individuals guilty of inciting electoral violence, as well as applying political pressure to the Nigerian government if it continues to reject accountability.

Along the same lines, and because no real democracy can exist without the rule of law, domestic and international pro-democracy groups should closely monitor President Buhari’s policies with regard to Nigeria’s judicial system, which many observers fear is being compromised by those who want to shield the election results from scrutiny.

Finally, civil society groups in Nigeria must resist the temptation to retreat into apathy and cynicism. We must not forget that serious and systemic change is a long-term process, and that the fruits of today’s efforts may take years to fully ripen. Initiatives focused on bringing more Nigerians—especially young Nigerians—into the political process should be encouraged. The Not Too Young to Run campaign, for example, which was launched by a coalition of youth organizations and successfully lowered Nigeria’s age limit for seeking office, is a crucial investment in changing the dynamic between Nigeria’s citizens and those elected to serve them.

Civil society must work to ensure close collaboration amongst its ranks and consistency in its values. This will help it sustain the respect and trust of the citizens, and it will make mobilization easier in the future. While international organizations and domestic civil society groups have an enormous role to play, ultimately, the country’s political landscape can only be reconfigured by a popular movement of Nigerian voters demanding reform. That is the promise of democracy—in Nigeria, and around the world.

Udo Jude Ilo is head of the Nigeria office for the Open Society Initiative for West Africa.