Q&A: How Marriage Equality Won in Costa Rica

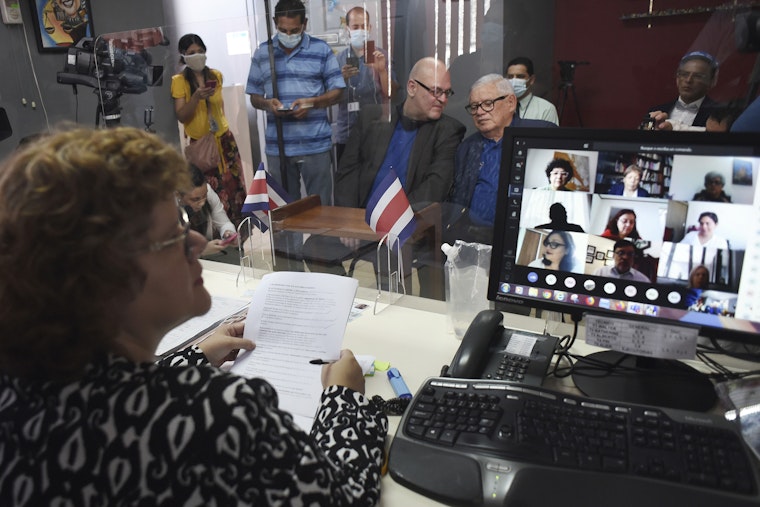

In the spring of 2020, after decades of organizing by activists and civil society groups, Costa Rica recognized marriage equality for same-sex couples. Recently, the Open Society Human Rights Initiative’s Gregory Czarnecki spoke with Nisa Sanz, a member of Movimiento Nacional por el Matrimonio Igualitario, a Costa Rican LGBT rights organization, about the victory.

When you think about the campaign, do any moments stand out?

Absolutely. Our campaign was a massive mobilization of LGBT people and allies at the grassroots level, and it took more than a year. It reached and mobilized a broad coalition—not just of civil society groups, but also of domestic and international corporations that supported our cause.

Do any specific challenges come to mind?

We faced a major challenge from a bill presented in the Legislative Assembly to create an alternative legal avenue to marriage. The bill would have recognized civil unions and provided patrimonial protections for couples, but it would restrict the legal concept of family and marriage exclusively to heterosexual unions.

This was clearly a discriminatory act that would have had devastating effects; it would have treated same-sex couples as an “arrangement” or “contract” of two adults, which is a much different thing than being a family. Thankfully, through relying on the breadth and strength of our coalition, we were able to defeat the bill—but only narrowly.

How did the COVID-19 pandemic affect the campaign?

The pandemic was used cynically by the opposition to try to delay adoption of the law. A conservative faction of the Legislative Assembly appealed to the Supreme Court of Justice of Costa Rica, asking that the court delay any action on this issue until COVID-19 was addressed. The court rejected the request, but did so in a way that left the door open to opponents of same-sex marriage. In response, we mobilized our allies to make sure their voices were heard by legislators. It was stressful, but it worked

When this campaign began, polling done by your group showed that less than 30 percent of Costa Ricans supported same-sex marriage rights. How were you able to succeed in such a challenging environment?

At the outset of our campaign, we conducted a survey to understand the starting point of our conversation with the public, and we discovered some important things. For example, about 25 percent of the population fully approved of marriage equality, while another 25 percent or so rejected it.

Most people, though, were in the middle; they favored legal protections for same-sex unions, but they had doubts about whether marriage was the right legal description of those unions. Many of these people often personally knew someone who identified as gay or lesbian, and they generally felt warmly towards this person. But they also reported that they had heard other opinions—mostly at church—that made them hesitate.

How did you reach them?

First, we made it clear that our campaign was not a threat to the church. We emphasized the fact that these were civil marriages, as opposed to religious marriages. This distinction went a long way in Costa Rica, where most people are Catholics.

We also emphasized the word “equal” as a way of underlining that the campaign was about addressing a form of discrimination. This was amazingly successful, to the point where even the anti-rights groups and media started to use it, when referring to our work. (See here, here, and here for Spanish-language examples.) And we focused on stories from real people who could speak authentically—no actors, no scripts—while also avoiding reference to “LGTBIQ+” in our materials and public statements.

Why?

We discovered that they confused the general public. Instead of hearing our message, they would be distracted by wondering what the acronym stood for. Similarly, we avoided using typical graphic elements related to activism—the rainbow flag, etc. We did this because we believed that our target audience was reachable if we focused on reminding them of the people in their own lives who’d benefit from the change; they weren’t trying to join a movement or become activists.

How do you build on this success?

It’s important to emphasize that we see passage of this law as the starting point, rather than the destination. Ultimately, what we’re fighting for is not simply legal equality but real equality—the kind of equality that manifests in daily life.

We’re working for a future where LGBT people who are in love are not afraid anymore to hold hands in public; where no one needs to worry about being fired from their job because of their sexual orientation or gender identity; where no kid is bullied simply for being gay, lesbian, or trans; where same-sex partners are understood to be equal members of any family.

Movimiento Nacional por el Matrimonio Igualitario is a grantee of the Open Society Foundations.