The Spy Files: An Interview with Eric King

By Becky Hogge

Events surrounding the Arab Spring may have highlighted the internet’s power as an organizing tool, but they have also exposed the scale of digital surveillance and censorship taking place in repressive regimes. Perhaps even more eye-opening than revelations about the extent of online surveillance in the Middle East/North Africa region is the fact that much of it is facilitated by products manufactured by Western companies.

In December 2011, the Open Society Information Program grantee Privacy International (PI), together with the UK’s Bureau of Investigative Journalism and WikiLeaks, released the Spy Files, a database of companies that manufacture and sell surveillance products. The project, part of Privacy International’s long-term investigation into the international trade in surveillance technologies, Big Brother Inc., was supported by undercover investigative work at industry trade fairs carried out by Privacy International’s Eric King. The launch of the Spy Files prompted major international television and newspaper coverage of the issues behind the export of Western surveillance technology to repressive regimes. Here, Becky Hogge speaks to Eric King about his work on the project, and about Privacy International’s plans for the future.

Can you speak a little bit about the work that went into launching the Big Brother Inc. database?

Over the past year I have attended a series of secretive industry-only surveillance trade conferences in London, Paris, Washington D.C., and Kuala Lumpur in order to collect as much information as possible on the companies selling surveillance technology. As there is very little publicly available information about this trade, we felt that this was the only way to obtain the raw accurate data we needed to assess the potential dangers of the way the surveillance trade is currently operating.

Why is it important to open up information about this industry in the way that you have done?

These companies are manufacturing and selling some of the most dangerous technologies in the world. For human rights activists, journalists, and political dissidents living under repressive regimes, the security of their communications and online activities is a matter of life or death—yet unlike the traditional arms trade, this area is almost entirely unregulated. The surveillance industry has relied for years on the fact that the technologies these companies sell are complex, and thus few people fully comprehend the ways in which they can be used (and abused). If we are to persuade policy makers, regulators, and legislators that this needs to change, we first need to foster a wider understanding of the situation.

What sorts of technologies are these companies making? And who are the victims of these technologies?

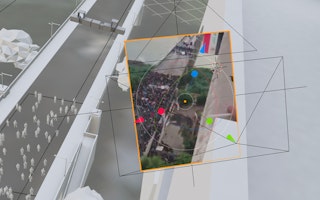

The variety and ambition of the technologies being manufactured and sold today is breathtaking. Devices small enough to be carried in a rucksack or briefcase that masquerade as legitimate mobile phone base stations in order to intercept and decrypt SMS messages and phone calls from all mobile phones within a radius of several hundred meters (“IMSI catchers”). These devices are marketed as being perfect tools to use during public order situations—allowing law enforcement agencies to unmask protesters without them even knowing. Sophisticated Trojans were marketed that, once installed in a mobile phone, allow the purchaser to remotely turn on the phone’s microphone and camera in order to record sound and take photographs of the phone’s location and user. Finally the “Optical cyber solutions” for mass surveillance of entire populations, involving tapping the submarine cable landing stations that carry all communications traffic in and out of countries. These techniques were originally developed by the NSA in the 1990s, and until now have been a closely guarded secret.

Is the market for these technologies being driven solely by repressive regimes?

The majority of surveillance technology companies are based in wealthy Western countries and exist primarily to fulfill domestic demands. Much of what they sell is dual-use, i.e. it can be used innocuously and it can also be used to facilitate mass surveillance and censorship. For example software that might be used as a spam filter in the UK could be used to block, or otherwise interfere with, emails containing the word “democracy” in Bahrain.

Given that this is the case, one might have expected these companies to exercise caution in selling such potentially lethal technologies—but instead most of them have been eagerly marketing their products to repressive regimes in the Middle East and Africa, and turning a blind eye to the consequences. Because of the lack of judicial or regulatory oversight and their willful disregard for human rights, these governments are effectively buying themselves unfettered access to every citizen's movements, activities and communications.

Some companies have gone above and beyond for their clients, like Area SpA, an Italian firm that built a sophisticated mass surveillance system in Assad's Syria. Area even flew teams of employees out to Damascus to construct a monitoring center under the direction of the Syrian secret police. After the project was exposed, Area quietly withdrew from the contract.

What can be done to stop the export of surveillance technologies to repressive regimes? What steps should governments take? What steps should civil society in the countries where these technologies are being manufactured take?

At the moment, companies wishing to export surveillance technologies from Europe or the US don't require any kind of export license to do so. This seems a strange oversight as the export of dangerous or potentially dangerous products is usually regulated in civilized countries—for example, European law forbids the sale abroad of instruments of torture, and in the UK it is illegal to export sodium thiopental (a drug used in lethal injections) to the U.S. The first thing governments ought to be doing is remedying this deficiency by putting in place proper export regimes to prevent the sale of surveillance technologies to governments intending to use them as tools of political control. After that, we can look more broadly at the ways in which the surveillance industry more generally should be regulated.

What can citizens and civil society groups inside these regimes do if they fear they are targets of these technologies? Is there anywhere they can go for advice?

We urge citizens and civil society groups living under repressive regimes to get in touch with Privacy International, if they think they can do so without endangering themselves. We have a wealth of information about the various tools that can be used to improve the security of your electronic communications and protect your location.

The surveillance systems used are very sophisticated, but they’re not perfect. For example, creating multiple email addresses using different pseudonyms, and using online anonymity tools like Tor, will significantly enhance your security and privacy, while leaving your mobile phone at home when you attend protests or meetings will help prevent the automated tracking of your location.

What are the next steps for this project?

The information we have uncovered thus far is just the tip of the iceberg. Many more companies are still operating under the radar, selling technology to governments they know will use it to facilitate torture, unlawful arrests, extrajudicial executions and other grave human rights abuses. We are looking carefully at the possibility of bringing litigation in the national or international courts against one or more of the companies whose products have been directly involved in harm to individuals.

The relationships between some of these companies and Western governments also deserve further scrutiny. While we await regulatory action on exports, we will strongly encourage the industry to self-regulate and ask companies to formally undertake to comply with human rights principles in their future dealings with governments and intelligence agencies.

Becky Hogge is a consultant for the Information Program at the Open Society Foundations.