With Upcoming Election, Tanzania Shows the Limits of “Good Enough Governance”

By Bram Dijkstra & Marta Martinelli

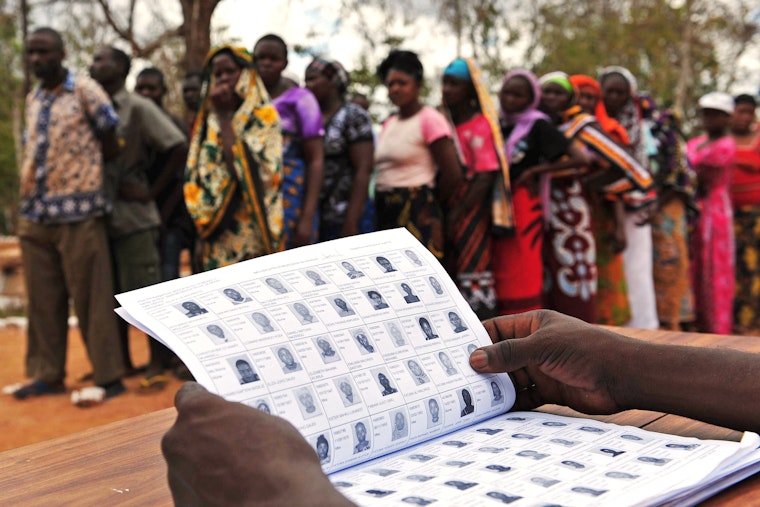

The October 2015 elections will be a true test of democracy in Tanzania. For the first time since the restoration of multiparty politics, a unified opposition has formed a credible threat to the 50-year hegemony maintained by the ruling party Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM). Yet as Tanzanians prepare to vote, Tanzania’s democracy shows signs of regress.

The European Union and the international community eagerly embrace Tanzania as a stable, peaceful, and democratic country in an otherwise turbulent region. And indeed, the country’s post-independence history has largely been free from the violent upheaval that continues to rock some of its less democratic neighbors. Its human rights–based foreign policy, compassionate treatment of refugees, and regional mediation role have earned it international praise. This peaceful stability has attracted donors, investors, and tourists alike.

Yet Tanzania’s “normalcy” risks obscuring simmering tensions. With two-thirds of its 50 million citizens living in poverty, few enjoy the benefits of the country’s remarkable economic growth, which has averaged around seven percent over the past decade. The Global Hunger Index places Tanzania second only to Burundi in the level of undernourishment in the East African Community. More than half of Tanzania’s youth, who comprise over two-thirds of the population, are unemployed.

Discontent over Tanzania’s uneven development has thus far not been reflected in electoral results. CCM, which has been able to peacefully extend its long-term rule into the democratic era, continues to enjoy significant advantages resulting from the country’s past as a single-party state. It can tap into firmly embedded party structures throughout all regions of Tanzania’s vast territory to influence voters at the grassroots level. It also benefits from a stable and substantial funding base, and holds strong control over state institutions. Because of CCM’s status as the liberation party, few Tanzanians questioned the party’s dominance in political life.

But it appears that the status quo may finally be cracking. Major opposition parties boycotted last year’s constitutional review process and joined forces to form an opposition coalition called UKAWA, a Kiswahili acronym for Coalition of the People’s Constitution.

Their protest centered on what they saw as an attempt by the ruling party to push through an unpopular constitution. Crucially, this draft rejected a reform of the Union, which would grant greater autonomy to the Zanzibar Isles, whose semiautonomous status presents a persistent challenge to national unity. To many Tanzanians, the stalled process revealed the lengths to which CCM is willing to go to quell calls for reform.

But in doing so, CCM may have overplayed its hand. The anticlimactic review process reinvigorated political life, repoliticized the Union question, and created high expectations about the freedom and fairness of elections. The electorate’s confidence in the potential of elections to bring about meaningful change has suffered, and after three years of popular debate, the sense of disaffection with and political misappropriation of the constitution has grown.

UKAWA is gaining momentum, especially since the appointment of former Prime Minister Edward Lowassa as its presidential candidate. The presidential hopeful was eliminated from the CCM nomination ballot, prompting a wave of further defections from CCM.

With less than six weeks to go, the electoral contest is heating up. CCM has been using its political clout to compound the structural barriers to free and fair elections. Timely and effective judicial remedies to challenge presidential results, as well as decisions of the National and Zanzibar Electoral Commissions, are absent.

Members of the commissions are appointed by presidential decree, making independence and impartiality virtually impossible. An imbalance in voter registration requirements between Zanzibar and the mainland, censoring of voter education material, and a controversial redrawing of electoral boundaries are further skewing an already uneven political field in CCM’s favor.

Recent weeks have also seen less subtle tactics of intimidation, harassment, and repression. All three major political parties have militias, which have been growing in force over the past several months, particularly in Zanzibar. If intimidation practices continue during the campaign period, with no judicial remedies to account for misconduct, Tanzanians may find themselves looking for other, less peaceful ways to express their grievances and settle disputes.

The European Union and the broader international community must use their influence to push Tanzanian authorities for a peaceful and credible electoral contest. But the EU should also remember its own long-term commitment to governance and democracy, which must go beyond the “good enough governance” of mere election support. Tanzania’s direct neighbors stand testimony to what happens when simmering tensions are allowed to fester.

Bram Dijkstra is an advocacy officer for Open Society–Europe and Central Asia.

Until February 2022, Marta Martinelli was head of the EU external relations team for the Open Society European Policy Institute.