What a U.S. Musical Tradition Can Teach Us about Roma Culture

By Mate Gaspar & Eleanor Kelly

The history of Roma people in the United States remains unfamiliar to most. Maybe even less familiar is the Hungarian-Gypsy musical tradition brought by many of those Roma to the United States over 100 years ago. A new book, Gypsy Violins by Steve Piskor, himself from a long line of Hungarian-Slovak Roma musicians, seeks to uncover this vibrant past and preserve it from sadly increasing obscurity.

The history of American-Hungarian music begins in Braddock, Pennsylvania, in 1887 with the influx of Hungarian-Slovak workers taking up the employment opportunities offered by Andrew Carnegie. Most of the Roma musicians among them came from Kassa, Hungary (now known as Kosice, Slovakia). Youngstown, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, and New York also became home to many of these musicians. Among the fans of cimbalom music—part of the Hungarian-Gypsy musical tradition—was Henry Ford.

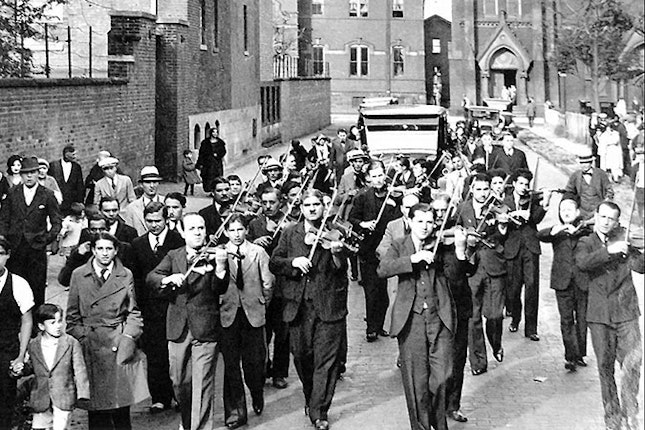

Gypsy Violins has collected scores of archival photographs of funerals, weddings, baptisms, parades, and celebrations in which this music played a crucial role. Many of the pictures have never been viewed by the general public. Also in the collection are over 200 pages of historically-significant newspaper articles.

In depicting a once thriving community, Gypsy Violins reminds us that the survival of cultures—however vibrant they may be—is never guaranteed. Though faded in the United States, in Europe today Roma culture perseveres despite a backdrop of state sponsored evictions, discrimination, and exclusion. This culture must be protected if the European Union is serious about its commitments to Roma, Europe’s largest minority of about 10 to 12 million people. “Who are you if you don’t know anything about where you come from, about your origins, your family, your language, your own culture?” reflected a young Roma man from Macedonia at a recent retreat on Roma pride.

Gypsy Violins preserves the culture of an old generation of Roma from obscurity and reminds a new generation of Roma pride in the past and what’s needed to protect this culture in the future.

Until January 2014, Mate Gaspar was the deputy program director of the Open Society Arts & Culture Program.

Until May 2021, Eleanor Kelly was the regional head of communications for the Open Society Foundations.