Yuri Orlov and the Legacy of Helsinki Watch

By Aryeh Neier

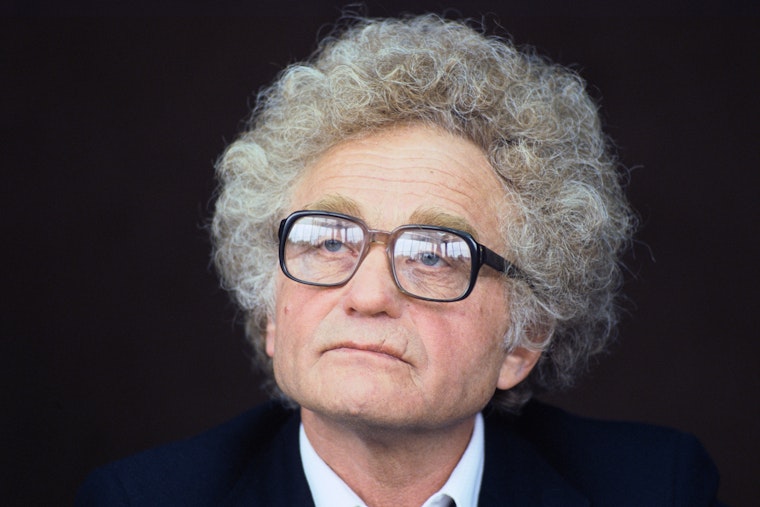

Yuri Orlov, a physicist who was born in the Soviet Union, died recently in Ithaca, New York, at age 96. He had lived quietly in Ithaca, where he had an appointment at Cornell University, since shortly after arriving in the United States under fairly dramatic circumstances in 1986. In the Soviet Union, Orlov had been a leading figure in that country’s small human rights movement. Indeed, it could be argued, his efforts on behalf of human rights played a significant part in changing the course of history.

This is all the more remarkable because his initial efforts to promote human rights did not go well. In 1956, when Nikita Khrushchev delivered his famous speech detailing Josef Stalin’s crimes, Orlov gave a talk at an open meeting of the Academy of Sciences calling for honesty and morality, and the need for democratic development. The Communist Party expelled him. He was fired from his job and forced to relocate to Armenia for 15 years to get employment. He eventually returned to Moscow in the early 1970s, where he made contact with other scientists who were becoming active in efforts to promote human rights.

In August 1975, the Soviet Union achieved what it considered a great diplomatic triumph. At a conference of 35 countries of Europe and North America in Helsinki, Finland, it secured the adoption of an agreement that it considered a kind of belated peace accord for World War II. The most important part of this achievement from the standpoint of the Soviet government was that it accepted the national boundaries that had been set in Europe at the end of World War II.

Recognizing the importance of the boundary issue to the Soviet Union, a few Western diplomats taking part in the Helsinki meeting were able to insert language requiring the governments signing the agreement to respect human rights. When the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted—without dissent—by the United Nations in 1948, the Soviet Union and the countries of Europe it controlled had all abstained.

The Soviet bloc countries also had not ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Yet the Helsinki conference’s so-called final act incorporated these agreements by reference, and included a provision asserting that citizens had a right “to know and act on their rights.” The final act thereby became the first international agreement in which the Soviet Union, and countries it controlled, such as Poland and Czechoslovakia, committed themselves to respecting human rights.

Proud of its triumph in securing the unanimous adoption of the Final Act by the 35 countries that attended the meeting in Helsinki, General Secretary Brezhnev’s government had the full text published in the country’s official newspaper, Pravda. That is how Yuri Orlov and some of his fellow rights activists discovered that the Soviet government had committed itself to respect human rights.

Orlov took the lead in creating an organization, the Moscow Helsinki Watch Group, which would document violations of the agreement that the Soviet Union had made at Helsinki. The formation of the group was announced at a press conference called by the Soviet Union’s most renowned physicist, Andrei Sakharov. Orlov became its chair. The group called on citizens in other countries that had signed the agreement to form similar bodies.

Soon, more groups focused on the rights provisions of the final act were formed in other parts of the Soviet Union—including Ukraine, Lithuania, and Armenia—and were operating independently of each other. In addition, a Polish organization, the Committee for the Defense of Workers, also took on monitoring violations of the Helsinki Final Act. Meanwhile, on January 1, 1977, the Charter 77 Group led by Vaclav Havel announced its appearance in Czechoslovakia with a stated purpose of seeking compliance with the Helsinki Final Act.

Though these groups were small, the emergence of a human rights movement—known as the Helsinki movement—in large parts of the Soviet bloc was recognized within those countries and internationally as a major development.

The Moscow Group quickly took on a number of significant issues involving abuses of rights in the Soviet Union. They included the use of psychiatry for political purposes to punish dissent, the rights of religious believers, the distribution of funds raised in other countries for the families of political prisoners, and the right of Jews to emigrate from the Soviet Union.

Inevitably, these efforts incurred the wrath of the authorities. Starting in early 1977, they cracked down. Most of the members of the Moscow Helsinki Watch were arrested and put on trial. Yuri Orlov was sentenced to seven years in a strict regimen prison to be followed by five years of internal exile in Siberia. The harsh treatment of the members of the Helsinki monitors in Moscow, and in other parts of the Soviet bloc, was widely publicized internationally. It inspired the formation of Helsinki Watch groups in a number of western countries, including the United States.

In 1978, I was one of those who helped found the U.S. branch of Helsinki Watch. George Soros was one of its first financial supporters, as well as a regular participant in the early Wednesday morning meetings that developed its strategy. George attaches a lot of significance to his participation in those meetings as they played an important role in his approach to promoting open societies.

In its early years, the foremost item on its agenda was securing freedom for members of the Moscow Group and for those imprisoned elsewhere in the Soviet Union and in other Soviet bloc countries. Over time, the U.S. Helsinki Watch evolved into a global organization, Human Rights Watch. Protecting those who try to promote rights in their own countries remains a central part of its mission.

Yuri Orlov served his full prison sentence of seven years and was in internal exile in Siberia in 1986 when an unexpected opportunity arose to secure his release. The Soviet authorities arrested an American journalist, Nicholas Daniloff, the Moscow correspondent for U.S. News and World Report, and charge him with espionage.

It seemed a reprisal for the arrest in New York of a Soviet diplomat in New York a few days earlier, also on charges of espionage. The two arrests produced furious reactions on both sides. Nevertheless, the two sides negotiated and agreed to an exchange of prisoners. Before the agreement was finalized, a State Department official contacted the U.S. Helsinki Watch and informed us that, as part of the deal for the repatriation of the two accused spies, it would be possible to secure the release of one persecuted dissident from the Soviet Union. Who did we choose?

It is very uncomfortable to make such a choice. While one person would be freed, many others in dire circumstances would be left behind. Of course, we were particularly concerned about Yuri Orlov, because he had been the principal founder of the Helsinki movement. We thought our choice of Orlov was also justified by reports we received that he was suffering from tuberculosis and required medical treatment. Orlov was freed.

I was one of those who went to Kennedy Airport to greet him. The crowd that gathered there included more journalists and camera crews than I had ever seen at any news event. When I met Orlov and spent time with him, I found that his sudden celebrity did not seem to affect him. He was a relatively small, modest, and friendly man, concerned particularly with his fellow dissidents who were still being persecuted in the country he had left behind.

Not long after he came to the United States, he was offered a post in the physics department at Cornell University. Though it had been a long time since he had been able to do any work in physics, he evidently had strong scientific credentials. It was not surprising that he went to Cornell. Members of the department, including its most eminent member, Nobel Prize winner Hans Bethe, had been in the forefront among scientists who had campaigned for Orlov’s release from prison. They were leaders of an organization called Scientists for Sakharov, Orlov and Sharansky. Scientists, like Orlov, had been the leaders of the human rights movement in the Soviet Union; and scientists elsewhere had rallied to their defense.

Since moving to Ithaca shortly after his arrival in the United States, Orlov had not sought media attention. He spoke out on human rights issues when called upon to do so but did not try to play a leadership role in the worldwide human right movement that he helped to inspire. He is little known to many who became active in the human rights movement in more recent times. Yet he deserves to be celebrated for his role in helping to create that movement and for the suffering he endured in reprisal for his efforts.

Aryeh Neier is president emeritus of the Open Society Foundations.