Angola: A Test Case for European Union Diplomacy

By Marta Martinelli & Saname Oftadeh

The European Union (EU) is committed to promoting democracy, the rule of law and human rights abroad. As a mineral-rich regional power, Angola poses a difficult puzzle for the EU. Although the EU’s traditional diplomatic leverage of development assistance may work with many countries in the region, it will have little purchase on Angola. The EU will need to find more sophisticated ways to promote its values.

The leadership’s resilience

Several factors constrain how the EU can engage Angola. First, it is a wealthy nation, attracting considerable foreign investment. Angola’s oil, diamonds and other mineral resources have ensured constant growth in the past years, and the World Bank expects GDP growth of 7.1 percent for 2013. The capital Luanda is also growing quickly thanks to the frenetic pace of construction. As a new Eldorado for foreign investors, Chinese, Brazilian, American, and European companies flock to Angola, eager to benefit from the country’s oil.

Second, the ruling party is convinced, and has convinced much of its domestic audience, that it deserves the loyalty and gratitude of its people. For the past decade, the debate on Angola has been dominated by post-conflict rhetoric. The MPLA (People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola—Labour Party, President Dos Santos’s party) has a dual political heritage: both as the liberation movement that fought the colonial power, and as the victor in the subsequent civil war. The government has made the most of this heritage. Going on to maintain the peace and rebuild the country’s infrastructure are regarded as major achievements. And the ruling party defines the country’s identity in opposition to “imperialist powers,” whom it accuses of trying to impose a western model of liberal democracy in the African continent.

Third, while the dominant rhetoric makes it hard to challenge Angola’s rulers on their legitimacy, the language itself also provides them with the protection of relative isolation. Angola’s relations are confined to lusophone countries, which limits the range of external partners who could voice critical opinions.

Fourth, Angola is considered a key player in terms of security in Central and Southern Africa: It has a geographically strategic position and its army is considered one of the strongest and most efficient on the continent. Angola’s intervention in neighbouring countries’ conflicts, together with President Dos Santos’s independent stand in face of Western powers, has also given him a certain level of credibility among other African leaders and has contributed to elevating the country’s international status.

Lack of progress for the general population

Unfortunately, Angola’s rapid economic growth has not been matched by progress towards social development and improvements in the democratic process. There is little reliable information on the precise amounts of oil production, oil revenues or spending of these revenues. Corruption is endemic and systemic in Angola, where power and wealth are concentrated in the hands of the ruling family and a restricted circle of oligarchs. As a consequence, the Angolan population is not benefiting from the country’s natural resources.

The recently established national sovereign wealth fund is meant to invest the oil revenue surplus to diversify the economy. But with the president’s own son, Jose Filomeno Dos Santos, as one of the managing directors, there is little hope for effective transparency or accountability, and it is unlikely that the fund is being managed efficiently. Inequalities in Angolan society show no signs of improving. The bulk of the population has no decent access to electricity, water, sanitation, housing, healthcare, food, and education. Over 77 percent of the population lives in poverty, and the under-5 child mortality rate is at 161 per 1000, significantly higher than in a number of other African countries with a much lower GDP.

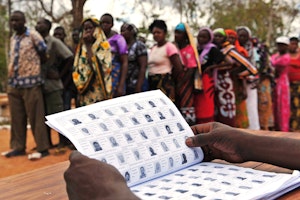

Elections in August 2012 gave a new five year mandate to President José Eduardo Dos Santos, who, after 33 years in power, is Africa’s longest serving president. But critical voices who have dared to challenge the government’s dominant rhetoric are silenced. Human rights activists report consistent violations such as lack of media freedom and harassment of journalists, restrictions on freedom of expression, information and assembly, mistreatment of youth groups, and disappearances of local diamond miners.

What can the EU do?

In 2012, a Joint Way Forward was signed to strengthen cooperation between the EU and Angola by reinforcing the “links between their commercial, industrial and financial actors”, and to establish “an intensive dialogue guided by the fundamental principles of democracy and rule-of-law.” The document makes provision for high-level meetings between EU and Angolan officials as well as for ad-hoc meetings with Angolan non-state actors. By including dialogue with Angolan civil society, which has only recently started to organize itself, the EU can help to foster new diverging voices able to challenge the government’s post-conflict discourse, such as those expressed in the 2011 youth protests. Because the Joint Way Forward provides for cooperation on mutually beneficial areas of action (such as economic growth, energy, and regional security), it will give the EU leverage to encourage increased and more open debate on and in Angola.

Internal EU developments can also help shape relations with Luanda. The EU is currently discussing a proposal to amend the existing Transparency and Accounting Directives. This would require EU companies exploiting natural resources in third countries, to publish all payments made to national and local authorities. If used consistently, the new legislation would help civil society organizations hold the government accountable for how income from foreign funds is spent. Curbing corruption related to oil revenues would help to loosen the ruling elite’s grip on political power. It would allow civil society to demand greater investment in public services. And increased transparency would make Angola a safer place to invest and increase the government’s internal legitimacy.

Angola is not just a test case in diplomacy to promote human rights, the rule of law and democracy. It is also a chance for the EU to show that it has learnt the lessons of the Arab Spring. Where the EU supports authoritarian regimes and maintains privileged relationships in exchange for economic, commercial, or strategic advantages, this has a severe impact on its credibility.

Until February 2022, Marta Martinelli was head of the EU external relations team for the Open Society European Policy Institute.

Until May 2013, Saname Oftadeh was a policy intern with the Open Society Foundations.