Life on the Margins of China’s Economic Boom

By Chuck Leung

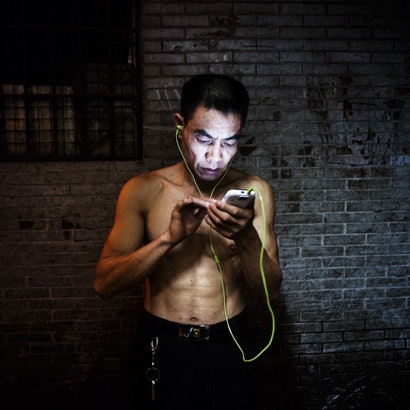

Photographer Sim Chi Yin, of VII photo agency, has been documenting those living at the margins of China’s rapid modernization. During a recent trip to Guangzhou, China, to continue this work, she spent time with a group of migrant construction workers, posting photos to Open Society’s Instagram account. She spoke with us about her project.

What drew you to this particular aspect of China’s ongoing transformation?

I’ve been working on China’s massive urbanization process for the past year and a half, looking at the landmark transition this generation of Chinese is making: from being a predominantly rural country to a largely urban one. I’m exploring what that change means both in physical landscapes and in people.

In Guangzhou, I’ve been documenting an urban village undergoing a lot of these changes. The migrant workers who live in the community are one part of that story. These workers come from the poorer parts of the country to build skyscrapers and new apartment blocks in the big cities, away from their families for most of the year.

It helps to put human faces to the vast and rapid urbanization we see all around us in China. I got full names of the migrant workers I spent time with, along with a little of their backgrounds and stories as far as I could, because I felt it was only respectful. And if we are trying to shed light on them and their work, one has to at least see, portray, and honor them as individuals.

Labor and migration have been long-term interests of mine. In my previous incarnation as a newspaper journalist, I was a labor reporter based in Singapore and wrote extensively about migrant workers there, culminating in a book about Indonesian women’s journeys from the villages to working as domestic helpers in places like Singapore, Malaysia, and Hong Kong.

In getting to know these migrant workers, how do you think they see themselves and their lives in relation to the kinds of changes you describe?

I think most are quite pragmatic about why they are migrant workers: it’s the best way they can see to earn more money for their families. The more thoughtful among them will articulate how they see themselves: as the essential force that has built today’s China, as the engine of the country’s phenomenal economic growth over the past three decades since the government allowed people to move around the country for work.

As one of the Hunan workers I hung out with, Xu Zhongshan, put it: “People think we migrant construction workers are dirty and sweaty, and some landlords won’t rent their houses to us. But really, if not for us, all these buildings around China today couldn’t have been built.”

Some of the work is hard and unpleasant—what in international NGO language is known as “3D work”: dirty, dangerous, and difficult or demeaning. But workers here—like migrant workers everywhere—are really survivors.

There was one day when I put on a hard hat and followed them into their worksite at what will be an upscale shopping mall in downtown Guangzhou. I watched them at work, using quite simple tools to do very heavy lifting: eight men hauling coils of thick electric cables up and down flights of stairs, climbing wooden ladders or anything they could find to make their way up into the ceiling boards to pull and lay the cables in place. On the other side of the hall, another group of workers hammered away, building the ducts for industrial-strength air-conditioning.

I came away with a deeper appreciation for the sweat and brute strength that goes into the making of the concrete towers around us.

What’s your personal perspective on these changes and their effects?

I’ve been in China seven years now and spend a fair amount of time talking to locals of different strata, getting a sense of the place, trying to understand the depth of society in its current state.

Overall, on the urbanization process, there are a lot of inequalities. I don’t think many Chinese, intellectuals or at the very grassroots, would dispute—even if they don’t want to say it to foreigners out of their sense of patriotism—that China today is a largely unfair, unjust society, and that often the individual at the bottom of the food chain has few tools to make his/her way up.

Government policies have shifted and tried to address some of the inequalities: for instance, in allowing migrant children to go to school in the towns and cities where their parents work. But in reality, many migrant parents you’ll meet will still tell you it’s a near-impossible task without the right paperwork, connections, and a wad of cash.

But, you know, many ordinary Chinese will lament all the problems they face, and then count their blessings that life today is a lot better than even 10 years ago, saying: “We can’t expect the government and country to change overnight.”

You’re active on social media. How do you think it has influenced or affected your own work, and the field of documentary photography in general?

Social media platforms are fun and provide visibility, helping the work get seen by a large audience. For me, since I work out here in Asia, it’s also a way to stay in touch with editors, clients, and friends in different parts of the world.

More documentary photographers value this direct interaction and self-publishing now, as less work gets published by mainstream outlets. I’m still not sure how they help in terms of actual distribution and monetizing the work though.

Instagram is an interesting animal. It’s good for sharing in an informal, diary-writing sort of way. I used to keep a journal and write religiously, so Instagram has allowed me to go back to some of those roots. Sometimes my captions are so long Instagram refuses to post them!

By nature of the medium though, the interaction it draws is often short-lived: a picture gets a surge of hits in the first 24 hours or so and then is “old news,” leading some to criticize it for promoting instant gratification. And sometimes the engagement does feel quite superficial. But it is an exciting means of self-publishing, and vast reach and direct interaction with one’s audience is a valuable and interesting experience.

Until November 2021, Chuck Leung was video producer for the Open Society Foundations.