After the Wall Came Down

In Depth

By Tim Judah

It’s been 30 years since the Berlin Wall fell, inspiring a democratic awakening throughout Central and Eastern Europe. What lessons does the Cold War’s end offer for the next generation of reformers?

A Journey

Some 30 years ago, I arrived as a young reporter in Bucharest shortly after the fall of Nicolae Ceaușescu, who had been executed with his wife on Christmas Day, 1989. Across Romania, I was witness to the upheaval of the months following the immediate collapse of the Ceaușescu regime—an extreme version of the struggles that unfolded across the region over the spoils of power.

Thirty years later, where does the region stand? The question is often presented as whether the glass has been half full, or half empty. The answer depends on who you are. Did you seize the opportunities of 1989? Were you or your town devastated by the collapse of Communist industry?

Statistically there is no debate. Since 1989, Poland’s GDP per capita has increased almost 700 percent. In Slovakia that figure is 635 percent, in Hungary, it is 324 percent.

In 1989, Poles could expect to live 71 years. Today their life expectancy is 77 years. Hungarians can expect to live six years longer than in 1989, Czechs almost seven. Some countries do better, some far worse, but everywhere the numbers show huge progress.

But people are not statistics. Capital cities are thriving, the middle class is prospering; the young cannot imagine a world without the freedoms they have grown up with. But, just as in the West, the wealth that came to some after 1989 has not been shared fairly. Services such as health and education have suffered, especially outside of the capitals and big towns, feeding resentment that provides fertile ground for nationalists and populists. And, while there have been increases in GDP and people are living longer, the same is true of the West. So, while the gap between the two halves of Europe has narrowed, it is far from closing.

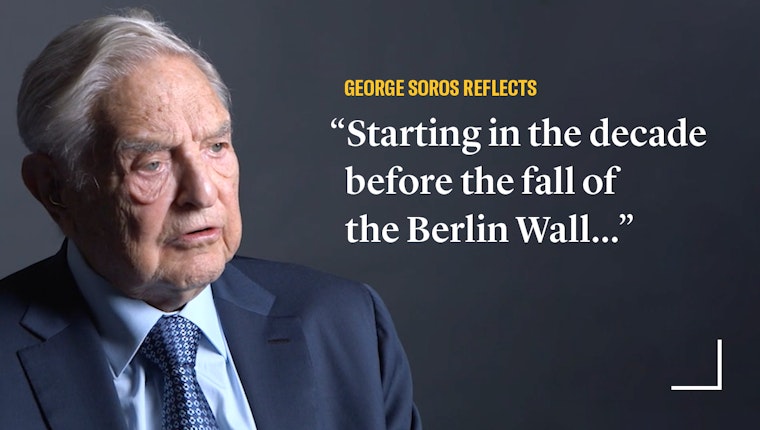

Now as the world marks the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Open Society Foundations asked me to look again at these questions. Open Society, led by its founder and chair, George Soros, clearly has an interest in the answers, having devoted a vast effort during the 1990s to support the newly emerging democracies of the region and to ease some of the pain of transition.

For more than two weeks in September, I travelled to Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Romania, to meet and listen to individuals who played a role in the dramatic days of 1989 and 1990—and to activists who were young children back then, but who continue to stand up today for the values of an open society.

In 1989, expectations were huge. But they were also unrealistic. Back in Bucharest again, I met Oana Popescu-Zamfir who runs GlobalFocus, a Romanian think tank; she argues that the race to catch up with the West after 1989 has created an inferiority complex too. There is “always the feeling that you are imitating someone” and that, 30 years later, there is always someone saying “you are still not good enough.” In Budapest, Anna Lengyel, director of the independent PanoDrama theater, argues that resentment has conjured up a “historical curse.” That means “a kind of society where the majority likes to be told what to do,” and to blame others for problems real or imagined.

In Prague, Marie Bohata, an economist, says the roots of many of today’s problems are that, in the wake of 1989, countries lacked laws suitable for modern market economies, which left niches that in turn created “a lot of opportunities for business practices”—and here she uses a distinct understatement—“which we could call ‘non-standard.’” Disappointment after 1989 was the realization that in the brave new world, “greed and selfishness” still existed, just as it had always done.

The advances of the nationalists, the populists, and the corrupt across the region have been well reported. But we have also seen people pushing back. Over the past months, in Romania, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic, tens of thousands of people have taken to the streets to protest against high-level corruption.

Martin Butora, who was a key figure in the changes of 1989 in the Slovak city of Bratislava, is elated when he sees people out on the streets once again, this time opposing today’s nexus of politics and organized crime. For him, it means there is hope for the future and that one legacy of the last 30 years remains strong: many countries that underwent transitions in the years after 1989 now have characteristics that can be found in any thriving democracy. Thirty years after the fall of Communism, many Central and Eastern European countries have myriad independent groups that can serve as a check on institutional political power and provide a voice for the powerless.

Thus, in Bucharest I met Marian Ursan, an activist who is preparing a brand new mobile shower van which will serve at least 1,200 people who are the most vulnerable—those who use drugs, are without homes, or are sex-workers and living on the streets. His team, supported by Open Society, works in hospitals to help the homeless (whom hospital staff often try to get rid of) assert their right to decent treatment—or their right to the documents they need to get treatment.

In Prague, David Tišer, also supported by Open Society, talks of how he and his colleagues staff helplines for young Roma who come out as gay and face hostility from their families and expulsion from their communities.

Since 1989, Europe has changed beyond recognition. Why study or look for work in your town if you can do so in Madrid or London? Freedom to work and travel has transformed the continent, creating possibilities and a bright future for millions, but leaving others suffering with grievances and bitterness. The exciting moment of 1989 has disappeared into the rear-view mirror of history. We are left with the legacy, and the challenge of the future.