An Overdue Reckoning with U.S. Torture

By Scott Roehm

In the fall of 2019, Axios reported that Don McGahn, when he was serving as White House counsel, had wanted to withdraw Gina Haspel’s nomination as director of the CIA because he feared her deep complicity in the CIA’s post-September 11 torture program would sink her Senate confirmation.

According to the report, U.S. President Donald Trump not only disagreed but “actually liked this aspect of Haspel's resume.” He thought her support for torture “was an asset, not a liability.” In fact, Trump apparently asked Haspel whether waterboarding “works,” and she replied she was “100 percent sure” that it did.

Of course, the president, who campaigned in 2016 as an avowed supporter of torture, could have once again been describing a conversation in the way he wanted to have had it, rather than how it actually transpired. Or perhaps Haspel indeed said something along the lines of what she’s reported to have said. Either way, for anyone who needed a reminder of how much work remains to be done to close this dark chapter of U.S. history, this anecdote should suffice.

On December 9, 2014, the Senate Intelligence Committee released a redacted executive summary of the so-called torture report: the 6,779-page Committee Study of the Central Intelligence Agency’s Detention and Interrogation Program. While reports of U.S. torture had been widespread—and highly controversial—for years, the executive summary was the public’s first meaningful look behind the curtain at the torture program that had McGahn worried about Haspel’s confirmation in the first place.

What the committee exposed was shocking. The program was brutal: one detainee, for example, had his “‘lunch tray,’ consisting of hummus, pasta with sauce, nuts, and raisins … ‘pureed’ and rectally infused.” He subsequently tried to commit suicide, twice. The program was also mismanaged and ineffective. For example, the CIA officer in charge of one secret black site prison described the majority of interrogators there as “mediocre” or “basically incompetent,” which he said was resulting “in the production of mediocre, or dare I say, useless intelligence….” And yet, as the committee described in painstaking detail, the CIA went to extraordinary lengths to propagandize torture as safe and necessary to save lives.

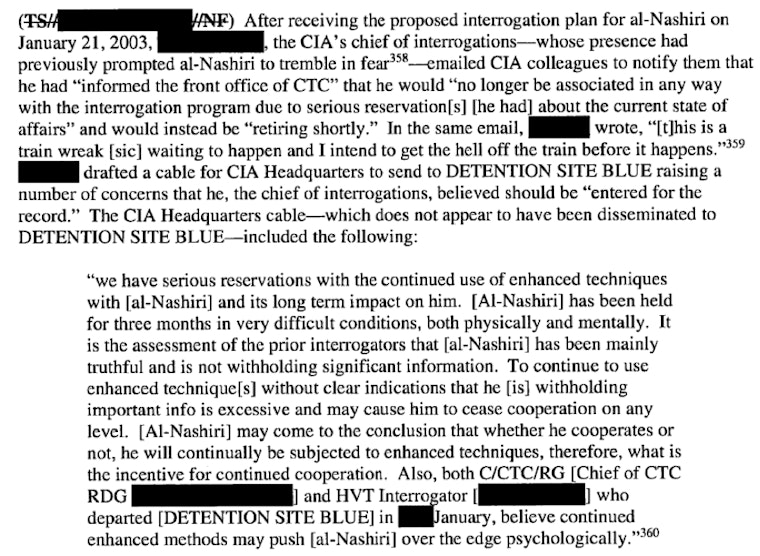

The executive summary is especially eye-opening for the emails, cables, and other internal CIA communications—which were never meant for public scrutiny—in which numerous CIA officers charged with implementing the program acknowledged its cruelty, lamented its inefficacy, and asked for the torture to stop. Here is just one example:

One might reasonably presume that what the Senate intelligence committee uncovered, in the executive summary alone, led to additional transparency, meaningful accountability, and widespread institutional reform. Unfortunately—save for the passage of one important new law—that has not been the case. Now, five years later, secrecy and impunity are still pervasive, and almost nobody in the executive branch has read a word of the full torture report.

Thankfully, much of this can still change, but it will almost certainly take the public demanding that it change and making clear that they will hold their political leaders accountable. Here’s where I would recommend such work begin:

First, the next U.S. president should declassify the torture report, make it public, and require government officials to identify both “lessons learned” and recommendations for reform. Remember, the executive summary, which is all that’s been made available to the public, is only eight percent of the report. The other 92 percent remains classified. Copies of the torture report that Senator Dianne Feinstein sent to executive branch agencies in late-December, 2014, have since been recalled, and remain locked away in a Senate safe. Before returning its copy to the committee, the CIA’s office of inspector general mistakenly reported having lost it, then having destroyed it. Full transparency is the only way to ensure that the torture report can never disappear for good.

Second, the next U.S. president should exclude from her administration anyone involved in managing, directly carrying out, or providing legal arguments for the torture program, or for torture in U.S. military custody. Involvement with torture should at least be disqualifying for public service, if not the basis for prosecution. Instead, as Haspel’s career trajectory shows, it has often led to promotion.

Third, for their part, foreign governments can and should make clear that they will not work with any U.S. official who was involved in the torture program.

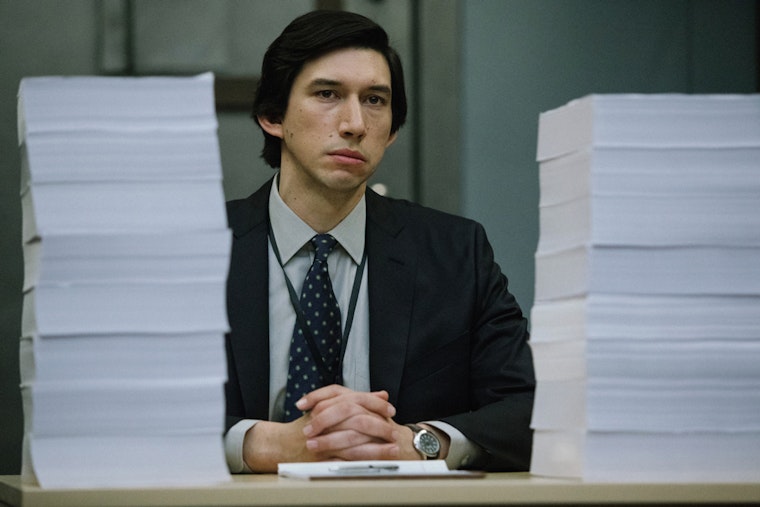

Fourth, everyone should go see The Report, and encourage others to do so. My organization, the Center for Victims of Torture, is not typically in the business of promoting Hollywood films, but this one is different. The Report is an honest telling of the CIA torture program and the long and difficult struggle in which the Senate intelligence committee engaged to investigate that program. Critical as the torture report’s executive summary is, congressional oversight documents rarely, if ever, resonate culturally. Movies, however, do. By helping foster a shared understanding about what the CIA actually did, The Report can play an important role in debunking myths about torture too often embraced by popular culture.

Lastly, as we press towards further truth and accountability, it is important for all of us to remember that torture is not an abstract concept; it cannot be perpetrated without a victim. In the case of the CIA program (and related torture in U.S. military custody), there were many victims. They deserve, and the United States is legally required to provide, redress and rehabilitation. Although these goals might seem, and might well be, largely unobtainable in the short term, it’s critical that we not lose sight of them over the long term.

Not long after President Trump nominated Gina Haspel to be CIA director, a colleague of mine who runs a torture-survivor-led torture rehabilitation program in the Washington, D.C., area wrote the following in an opinion piece for the Washington Post: “In the United States, the words we use to oppose unjust policies will not lead to our being jailed or tortured. I would urge all people of conscience to speak out for those who are not free to do so without fear of retribution or harsh punishment.” Let’s all heed his call by doing the hard work necessary to make sure, in the words of Senator Feinstein, that anything like the CIA torture program “will not be contemplated by the United States ever again.”

The Center for Victims of Torture is a grantee of the Open Society Foundations.

Scott Roehm leads the Center for Victims of Torture’s policy work and office in Washington, D.C.